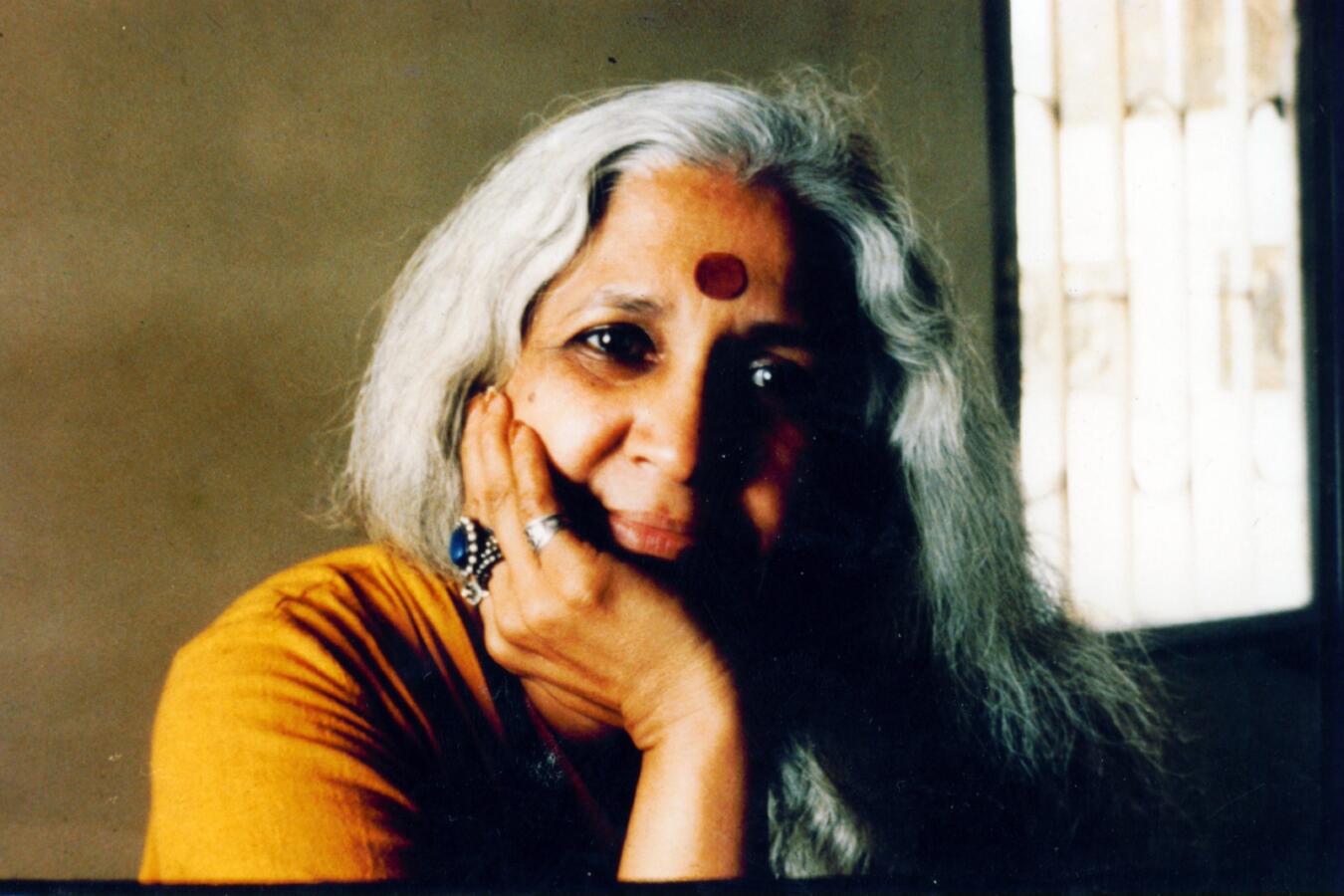

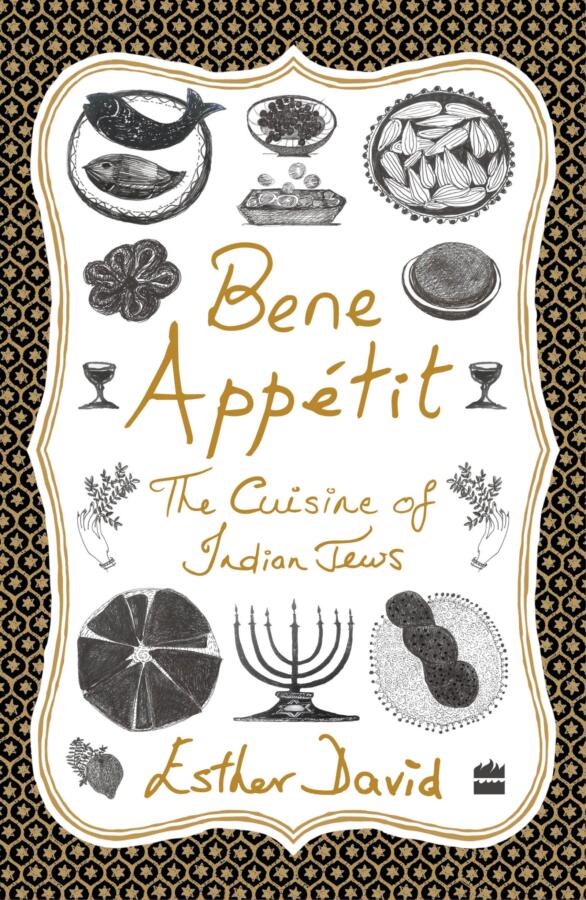

For Esther David, a renowned Indian Jewish writer from Ahmedabad in the Gujarat state of West India, food is culture, and it bonds communities and families. Her 2021 cookbook “Bene Appetit – The Cuisine of the Indian Jews” compiles the recipes, culture and lifestyles of Indian Jewish communities.

India, once home to over 50,000 Jews, now has around 5,000 families. Its communities are dwindling due to migration — the majority of the Jewish population migrated to Israel after 1948 — and smaller families. Indian Jews span the continent, from the Bene Israel Jews of western India, the Baghdadi Jews of Kolkata (formerly known as Calcutta) in Eastern India, the Cochin Jews in the south, the Bnei Menashe Jews of Manipur in the northeast to the Bene Ephraim Jews of Andhra Pradesh in the eastern south.

“Most probably Cochin Jews came to India from Persia after the destruction of the Second Temple before the Christian era. It is also believed that a few came from Spain,” Esther explained. Kolkata’s Baghdadi community, however, are descendants of Iraqi and Persian Jewish merchants who settled in the area in the 18th and 19th centuries. “Bene Israel came to India over 2,000 years ago,” said Esther. “They fled from Greek persecution and their ship was damaged near the West Coast of India. Their lifestyle is greatly influenced by local cultures, like the use of coconut.”

Each community’s traditional recipes are unique, aligning with Jewish dietary laws but also influenced by locally available ingredients. These traditional recipes, however, are becoming lost to a younger generation who adopt shortcuts. David, a Bene Israel Jew, set out to document these disappearing recipes — and translate them into English — in the hope that she will inspire all generations of Jews to return to their roots. This was a mammoth task, involving travel across cities and villages, visiting synagogues and meeting community members.

The Nosher celebrates the traditions and recipes that have brought Jews together for centuries. Donate today to keep The Nosher's stories and recipes accessible to all.

The cookbook includes vivid descriptions of synagogues, such as the Pardeshi Synagogue at the Kochi Fort in Kerela with its blue tiles, intricately designed wooden ceilings, bright paint and floral designs, in addition to details of how each community marks Shabbat culinarily.

Challah, for instance, is only available in Kolkata; Jews in Cochin use chapati (hand-rolled wheat flatbreads) or appam (flatbreads made with fermented rice) instead. The Baghdadi Jews of Kolkata also prepare a slow-cooked dish for Shabbat lunch called t’beet, consisting of a whole chicken stuffed with spiced minced chicken and rice, popular in Iraqi Jewish communities worldwide. Every Indian Jewish community uses sherbert — a sweet-sour juice made with crushed blackcurrants or grapes — for kiddush on Shabbat, as kosher wine is not available.

David identifies that one of the main reasons for traditional dishes disappearing is how time consuming they are. Take chick-cha-halwa — a Rosh Hashanah coconut-milk-based candy with a jelly consistency beloved by the Bene Israel community — that takes 15-18 hours to make! The Bene Menashe Jews of Mizoram forgo the candy for an equally time consuming Rosh Hashanah seder with sauteed fish heads, pomegranate seeds, almonds, stir-fried pumpkin slices, fried onion roots and a gravy-based chicken or fish dish served over rice. The Bene Israel community share the custom of consuming fish heads; theirs are marinated in lemon juice and red chili powder then shallow fried.

Holiday dishes are a true celebration of each community’s unique culinary culture. Spices such as cloves, cardamom, cumin and fenugreek are integral to almost every recipe of the Cochin Jews in Kerala — a state known for its spices. On Sukkot, they make pastel, crescent-shaped hand pies filled with shredded chicken flavored with cinnamon, black pepper, and turmeric, among other aromats.

On Hanukkah, instead of latkes, the Bnei Menashe Jews of Manipur make fried lentil or chickpea fritters. And alongside the globally recognized items on the Passover seder plate, the Bene Ephraim Jews of Andhra Pradesh include dates, apple and radish paste and homemade wholewheat matzah or chapatis.

Perhaps the most distinctive dish comes from the Bene Israel community, who created an edible way to mark celebrations — from weddings to holidays — called the Malida platter. Made up of sweetened, flattened rice and a variety of fruit, including bananas, apples and dates, then adorned with red roses, dried fruit and shredded coconut, it’s an integral element of their culinary cannon.

David offers us a fascinating, delicious glimpse into a world that is at once familiar and completely foriegn. “Bene Appetit – The Cuisine of the Indian Jews” is a celebration of the breadth and intricacies of Indian Jewish cuisine — and Judaism in general, while serving as a cautionary tale, reminding its reader of the importance of preserving tradition and of taking the time to learn the stories and practices of our ancestors.