I recently had the pleasure of coming face-to-face with an archivist’s nightmare: silverfish. Tiny, many-legged insects that feast on paper and books and thrive in dark, damp spaces. (Really—a nightmare.) I happened to encounter these dastardly creatures one afternoon as I was exploring the organ loft of historic Temple B’nai Israel, a beautiful synagogue in Natchez, Mississippi.

I work with the Natchez synagogue as part of my job: Director of Heritage and Interpretation at the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL). I attend meetings, work on grants, do lots of “preservation work” from afar… but sometimes I’m right up close to the preservation efforts.

When I got to the building, I opened a door to a tiny attic room and saw a pile of sheet music on the floor. I shined the light from my cell phone onto the pages and saw late nineteenth- to mid-twentieth-century Jewish liturgical music, rotting and covered in mouse droppings. I saw crumbling pages clearly being eaten by insects. I lifted a corner and there they were: silverfish, scrambling to escape the light. I shuddered and shut the door, vowing to return with gloves and plastic bags.

Standard archival protocol dictates that the best place to store historic documents is not, in fact, loose on the floor in a dark, damp, non-temperature-controlled-attic. Protocol also dictates that archival materials potentially infested by insects must be tightly wrapped and frozen for a period lasting somewhere between 72 hours and “a few months.” Having seen the silverfish with my own two eyes, I was certain: there was a freezer in my future.

I returned to Natchez a few weeks later, having purchased nitrile gloves, surgical masks, and all the extra-large freezer bags my local Kroger had in stock. I dove in, starting with a box of books I found covered in mouse droppings. It was…unpleasant.

Though the work was unglamorous, I saw results quickly as I brushed off the dust, smashed silverfish and cockroaches with my sturdy clogs, and bagged books as tightly as I could. It took a few hours to package all of the paper items in the organ loft and its two adjoining rooms. Patterns began to emerge, and I hummed to myself as I thumbed through prayer books and song sheets from over a century ago.

The process got me thinking.

Western music notation is like a secret language. The dots and dashes and strange squiggles communicate ideas and emotions so efficiently that it’s difficult to imagine any other way of representing that same information on paper (this is not, of course, the only way to write music). Being able to read music – and even write or arrange it – feels like a privilege. I love that I can flip through these songbooks, looking at pieces I’ve never seen before, and catch glimpses of what the choristers who sang these tunes might have sounded like standing in this organ loft a hundred years ago.

But there are other pages in these piles of decaying documents that speak even more to the language that these far-off singers and I share. I found song lists for services from 1926, 1955, 1972, listing parts of the service, page numbers for accompanying music, and names of soloists. It’s a format I’m familiar with as a person with extensive experience with liturgical singing (the experience of being the only Jew in the Trinity College Dublin Chapel Choir is a subject for another blog post). You shove the typed list haphazardly in the left side of your music folder, reference it throughout the service, and scribble on it when things change at a moment’s notice. It’s a humanizing document that offers evidence of the frenzied effort that bubbles below the surface of a traditionally stoic liturgical choir.

Of course, these choir members and I share another language – the language of Judaism. In many ways it runs deeper than the experience of being a musician, but it is the same in its humanity, in its shared symbols and notations and traditions. There is music, in it, too.

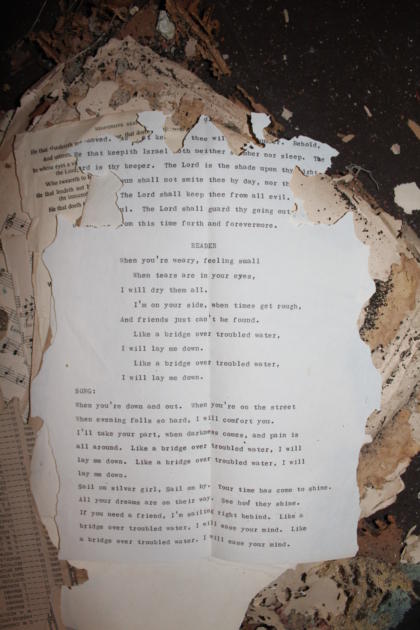

Toward the end of my archival project, I found another piece of paper, folded in half so that the insect damage was mirrored on each side of the page. At some point in the past – presumably after 1970 – a Temple B’nai Israel service had included a call-and-response singing of Simon & Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” Another glimpse into the past, another moment of imagined companionship with choristers who have long since left their posts in the organ loft.

I’m so glad I could sift through their music, even if I have to keep it in a freezer for a little while.