When working with the teenagers in my congregation, the teacher (i.e. me) is often learning from the students, and this past couple of weeks have been no exception. At the beginning of their confirmation year, our 10th graders are invited to think more deeply about what Jewish identity is and what it means to them.

This past week, we were exploring Jewish denominations as a way to begin understanding the many expressions of Judaism, as well as learning about some of the origins of these denominations and what they were responding to. The students are presented with several boxes, each containing a list of statements that have been taken from movement websites or the equivalent page of a rabbinic organization that serves that movement. The students check off the boxes of statements that most align with things that they would choose to articulate about their Judaism.

In a Reform congregation, it is perhaps not surprising to find that most of my students found themselves most resonating with boxes that represented the Reform, Reconstructionist, and Humanist branches of Judaism. But my favorite response came from one student, whose name I’ve changed for the purposes of this article, who said, “I need a Brian box.”

‘And what would you put in your Brian box?’ I asked.

Now, given the nature of the exercise, one might have assumed that what would follow would be a desire to mix and match some of the statements from a variety of the boxes on the page before him. But that was not what Brian had in mind at all. Rather, he said:

I think what goes in the box is going to be different at different times. It is going to be whatever I’m doing in different Jewish settings with different Jews.

“Oh,” I responded. “So are you saying that it’s the experiences that you have or create in a Jewish context that define your Judaism rather than a set of pre-defined principles?”

Brian concurred, as did several others in the class. We also agreed that there might be underlying principles that would have some determining factor on whether we felt like we belonged in a particular group or context (such as equality of men and women, the inclusion of LGBT Jews, which are values that are deal-breakers to many of our teens).

This way of describing belonging within Jewish life didn’t surprise me. Just a few weeks ago, I was brainstorming ways of experiencing the Jewish New Year with one of my adult stepchildren as she navigated life in a new city that came with a new job. We both spent less time focused on what institution was doing the offering, and more time evaluating what would provide an engaging and meaningful experience. She ended up going to two really wonderful gatherings, one based around a meal and ritual in someone’s home, and one with a Modern Orthodox rabbi who is doing some really out-of-the-box gatherings to engage young Jews in thoughtful conversation in non-conventional spaces.

These insights matter to me as a congregational rabbi serving a congregation affiliated with one of the legacy movements, because it is instructive when it comes to considering not only what we offer as a venue for meaningful Jewish experiences, but how we communicate about that in ways that respond to this kind of seeking. For those used to more traditional definitions of Jewish practice, we might wonder about where the sense of commitment is to sustaining communities, or the sense of obligation to certain ritual practices, holy times, and mitzvot (commandments) might be. Engaging in the latter can be deeply meaningful to our outside-the-box Jews when integrated into the experiences we create with them. They are not, in and of themselves, however, what will drive the desire to engage in the experiences in the first place. A prayer service in which people sit through a passive experience and then leave is not an immersive experience, regardless of how beautiful the music is or how well-crafted the sermon is. Embedded in an opportunity to connect socially and informally, guided to have a thought-provoking conversation with others, or given time for meditation and reflective space for individual spiritual soul-searching… these are just some of the elements that might enable a more immersive experience to unfold. These kinds of experiences are taking place all the time within legacy institutions, but we don’t always do a good job of communicating effectively about these opportunities.

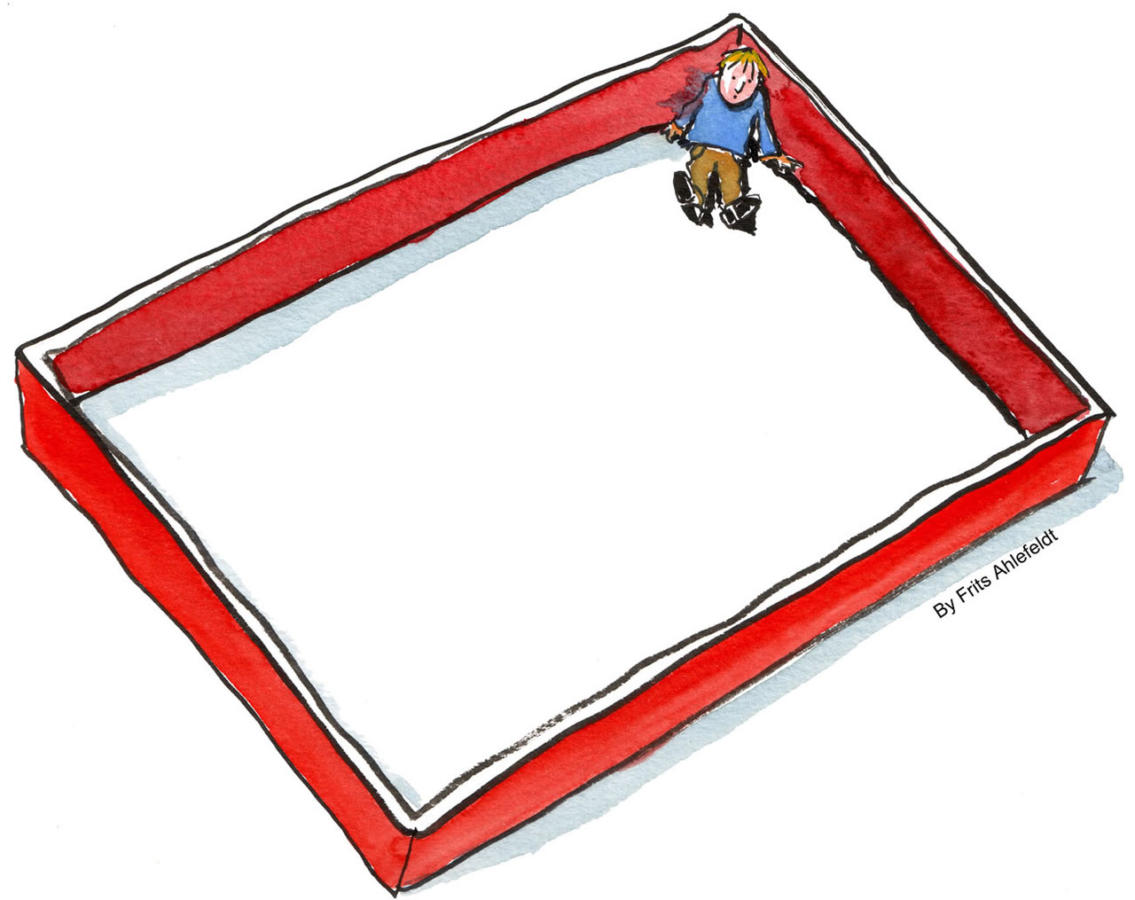

And the truth is, this is not just important for engaging those who are intentionally seeking something outside of the more conventional boxes. The insights of one 16-year-old young man reflects, I believe, the vast majority of Jews who are choosing how to live their Judaism. We all want to be inside the experience. The vessel/box/institution is just the potential container. If we spend too much time trying to preserve the container than crafting the experiences, we shouldn’t be surprised if we find our containers are feeling empty.