We all know how it feels to be sick. What I didn’t realize until recently is that what scientists call “sickness behaviors” – lethargy, self-care and social withdrawal – can have vital social and spiritual purposes, if we pay careful attention.

“Sickness behaviors” are among the ways that bodies are hard-wired to protect themselves. For instance, instinctively we “baby” a twisted ankle to minimize the risk of further injury. In 1979, scientists reasoned that sick people lose their appetites because reducing iron intake can help fight infection. It turns out that feeling bad can have physical advantages to help heal.

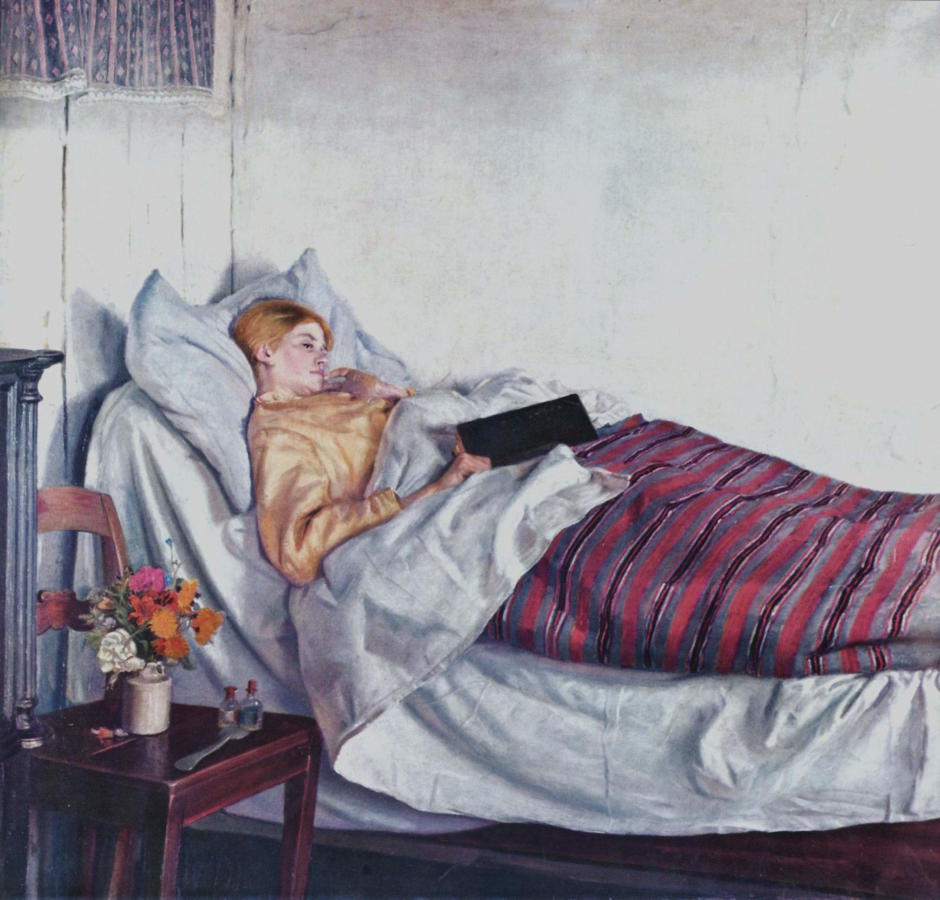

Feeling bad also can herald social and spiritual benefits, though these can seem less clear. Someone who feels sick often withdraws from one’s usual pace and activities. Feeling unwell, tired and sad are “sickness behaviors” that get the sick person’s attention to focus on self-care. These same behaviors also signal to others that someone needs attention and care, which can trigger our altruism. “Sickness behaviors” are evolution’s cue to pay attention to others, because a group that pays attention to each other is stronger and healthier together.

This altruism cue only works, however, if we pay attention to it. It used to be easier to pay attention – and notice who’s missing, who seems withdrawn and who seems “off” – when we lived in smaller groups more intimately connected to each other’s activities. Modern life, by contrast, often disconnects us from intimate and intuitive awareness of others, barraging us with constant demands for attention that can inure us to these built-in altruism cues.

Talmud records the Jewish spiritual teaching that the divine presence we call Shechinah dwells on each sickbed (B.T. Nedarim 40a). A sick person might withdraw from society, but can never withdraw from the holy. To the contrary, the sick person inherently is a focus for the holy, for the divine presence.

Putting Talmud together with behavioral science, we learn that what’s holy is precisely this call to pay attention to the withdrawal, malaise, low ebb or “off” energy we sense in another. While we might muscle through and shrug off these sometimes subtle cues, we – and each other, the world, and the cause of holiness in the world – would be far better off if we allowed ourselves the subtlety of paying this kind of attention, and allowing our natural altruism to well up.

What does this mean? It means raising our emotional and spiritual antennas a bit more. It means following our instincts and gently asking how someone is – not prying, but checking in. It means acting on our altruism; if we are managers, it means giving permission to be sick – not excessively self-indulgent, but humane and human. Most of all it means paying attention and making a priority of paying attention.

After all, the subtle inward turn that this kind of attention asks might just lead us to a very holy place.