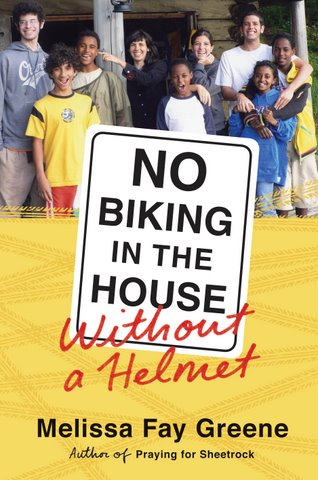

Melissa Fay Greene is the author of No Biking in the House Without a Helmet. She will be blogging all week for the Jewish Book Council andMyJewishLearning‘s Author Blog series.

In Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in November 2001, I pulled up to the gates of the compound of the Beta Israel people (disparagingly known as Falashas [strangers]), hoping to be admitted, along with my brand-new daughter,

to Shabbat morning services.

Arriving among these religiously-observant and destitute people, of rural origin, by taxi rather than on foot was likely to make a poor impression. But I’d known no one in the area to ask for Shabbat hospitality and my hotel stood half a city away from this dusty ramshackle neighborhood of mud huts and corrugated tin roofs. It was my first trip to Ethiopia. I’d flown seven thousand miles to report for the New York Times Magazine on conditions among some of Africa’s orphans of HIV/AIDS (which eventually gave rise to my book,

There Is No Me Without You

(Bloomsbury, 2007) and to meet a five-year-old girl named Helen, whom my family was adopting.

We were an American-Jewish family of seven, living in Atlanta; we had four children by birth and one by adoption from Bulgaria. The year the children were 6, 9, 13, 17, and 20, I lingered at the sunny kitchen table one morning and read in the newspaper that the United Nations was calling Africa “a continent of orphans.” Fourteen to twenty-five million children had lost one or both parents to HIV/AIDS. I read those pages not only as a concerned world citizen, but as a journalist, and as a mother aware that a perfectly good twin bed upstairs was going unused. “Could I write about this?” I wondered. I’d only stepped foot in Africa once, in Morocco, in my 20s. “Can you adopt from Africa?” I also wondered. “Can you adopt one of the fourteen to twenty-five million orphaned children?”

Aware of Israel’s airlift of 20,000 Ethiopian Jews to Israel in 1984 in Operation Moses (Mivtzah Moshe) and another 15,000 in Operation Solomon (Mitzvah Shlomo) in 1991, I located online an organization called the North American Conference on Ethiopian Jewry [NACOEJ], which helped support Jewish organizations in Addis. I phoned their New York office and asked, “Are any of the Jewish children orphans in need of adoption?”

The answer was yes, there were orphans, but no, they were not available for adoption. NACOEJ’s mission was to bring the people to Israel. They told me of an American orphanage in Addis, and I phoned there next, asking the same question in reverse: “Are any of the orphans Jewish?”

“They may be,” I was told, “but many don’t know what they are. We have a quarter-of-a-million orphans here. Is that your only criteria?”

By November I was on a plane to Addis: the New York Times had commissioned a story; and my family had been matched with Helen, a tiny, bright, and darling (non-Jewish) girl who’d lost her father when she was two, and her doting mother just a few months earlier.

Our first afternoon together in Addis Ababa, I took Helen shopping for new clothes, including shul clothes, and watched as she stepped out of her dusty orphanage jean overalls and into a complicated plaid wool jumper, a white blouse with a lace collar, and a royal blue corduroy jacket with brass buttons. Curly yarn sheep were affixed to the jumper and jacket. The ensemble seemed designed to be worn in Scotland at Christmastime rather than on a dry African plateau in 90-plus-degree heat to a jerry-rigged local synagogue. While I paid for the outfit and a new pair of sandals, she hopped beside me in excitement.

Helen wore her new clothes that Saturday morning as our taxi parked outside the Jewish compound. Half a dozen young men—guards—surrounded our car and looked through the windows. Helen scooted under my arm in shyness. Our driver got out of the car to explain that I was an American Jew hoping to attend services. Arguments seemed to follow, with a lot of gesticulating, while more young men jockeyed for a closer look at us through the windows. I rolled down the window to greet them with my paltry number of Hebrew words. I displayed my Chai necklace, but they turned away. The discussion grew heated outside the car, until the taxi driver got back in to report that the guards did not think I looked Jewish. The child looked Jewish, but I did not. If only I’d brought a letter from a rabbi or from the Israeli embassy in Ethiopia, they would have welcomed me happily; but, without anyone vouching for me, they were obliged to turn me away.

In America, I look Jewish. In Ethiopia, I did not look Jewish. In Ethiopia, Helen looked Jewish. But, in America, Helen does not look Jewish. She has borne this bravely, while embracing Judaism with a full heart.

In my book, I describe preparing Helen for her conversion to Judaism at age six, including a visit to the mikveh. Jesse, then age 7, tried to explain:

Jesse had loved converting to Judaism! Well, he hadn’t loved the in-hospital under-total-anesthesia circumcision, but he didn’t really remember it. He had loved going to the mikveh. To attain a state of ritual purity, religious men and women disrobe and immerse themselves in a cistern, a natural spring, a flowing river, the ocean, or a very small indoor pool. Jesse fearlessly, nakedly, cannon-balled into the water of a tiled mikveh at a local synagogue under the gaze of an Orthodox rabbi; he immersed himself the required three times, and for good measure did a somersault, his little white butt flashing briefly above the water line.

Now, in the back seat of the car, he excitedly prepared Helen for her visit to the mikveh. “The blue-green water will cover all your body and make you Jewish!” he enthused.

“Really?”

“Yes! You take off all your clothes and you jump in!”

“Wait. You take off all your clothes?” she asked.

“Yes! And you jump in the blue-green water!”

“And the rabbi’s there?”

“Yes.”

“Then I’m not taking off my clothes.”

“Yes, you have to,” he insisted. “The blue-green water touches every part of your body and makes you Jewish.”

“I’ll wear a swimsuit,” she said.

“You can’t! Right, Mommy? You have to be naked so the blue-green water can touch every part of your body and make you Jewish!”

“I am not taking off my underpants.”

“You have to!” he said again, alarmed by this unforeseen obstacle. (In fact, it would be conducted with modesty and privacy.) Jesse was nearly weeping now: “The blue-green water has to touch every part of your body to make you Jewish.”

“Forget it,” Helen pronounced, looking out the window to end the discussion. “I am wearing my underpants.”

“FINE!” yelled Jesse. “Fine! But your BUTT is NOT going to be Jewish!”

Though Helen had been reassured of the modesty of the mikveh ceremony, she nevertheless panicked when the big day was upon us. She refused to emerge unclothed from the dressing room. “I don’t need to do this! I’m already Jewish!” she cried through the closed door. “My mother was Jewish!”

“Helen, REALLY? How do you know?” my husband and I called back.

“Because we always celebrated Chanukah!”

“OK, sweetie, hang on, let us ask the rabbi.”

The rabbi laughed merrily. “She picked the wrong holiday!” he said. “Ethiopian Jewry is older than Chanukah. If she’d said Sukkot, we’d have had something to talk about.”

“Helen, no, you’re not Jewish, come out!” we called, and she came.

She’s been trusting us ever since. She believes us that not all Jews are white people, although she was the only child of color in Religious School (until a family arrived with an adopted biracial daughter). She was the only child of color at her Jewish sleepaway camp. She was a gorgeous and historically-accurate Queen of Sheba (who was from Ethiopia) in Atlanta’s Purim parade. She helps make Shabos every Friday night. She davened so beautifully and hauntingly at her bat mitzvah, and then at her younger brother’s bar mitzvah—leading the Torah service, reading from the Torah, chanting the Haftorah, leading Minchah—that elderly men wept and asked where she’d been all their lives.

When Helen has outgrown her Jewish sleepaway camp, we will be happy to send her to Israel for travel and study, like her older siblings have done. I believe it will be obvious to everyone in Israel—teeming with Ethiopian Jewry—as it is obvious to us and to our congregation: this is what a Jewish child looks like.

Melissa Fay Greene‘s No Biking in the House Without a Helmet, is now available. She will be blogging here all week.

mikveh

Pronounced: MICK-vuh, or mick-VAH, Alternate Spelling: mikvah, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish ritual bath.

Shabbat

Pronounced: shuh-BAHT or shah-BAHT, Origin: Hebrew, the Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

shul

Pronounced: shool (oo as in cool), Origin: Yiddish, synagogue.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.