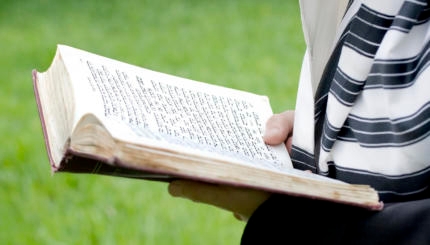

I remember Yom Kippur when I was 13. I was in synagogue, proudly wearing the

tallit

I had been given for my bar mitzvah some months earlier, sitting with my family in the seats we traditionally occupied throughout the High Holidays, four rows back from the

bimah

and the Ark where the Torah scrolls were kept. It was the Ne’ilah service, the closing moments of the holiday, and the congregation was rising for one final recitation of the Vidui, the collective confession of sins. With the infamous words of Leviticus 18:22, part of the traditional Torah reading for Yom Kippur afternoon, still ringing in my head, I too stood up and began to recite the litany out loud along with everyone else. But one sin, one above all, spoke up and demanded I confess it, repent from it, and pray for divine forgiveness: the sin of being a transgender person.

“For the sin that we have committed against You by identifying with a gender other than that which we were assigned at birth” isn’t part of any confessional liturgy I ever learned—it was more like “For the sins which we have committed against You both in the open and in secret”. But it didn’t matter that I could barely even express what I was thinking. I placed my hand over my heart, struck my breast, and begged God to forgive me for all the indiscretions within me: for desiring more than anything to be someone or something other than what I was, for having failed to fulfill the divine plan for me, whatever it was, for not having been strong enough to resist my yetzer ha-ra, my inclination to do evil. I prayed fervently, cried a little even, wishing that God would take away my transgender nature, and hoping He would make me, well, normal. Somehow.

The recitation of the confessional ended, and shortly the service came to a close with the words Adonai Hu Ha-Elohim, “The Lord is God”. The final shofar blast was sounded, and I remembered the verse: Vayomer Adonai solachti ki-d’varecha, “And God said: I have forgiven, as you have asked,” and I knew—or really thought I knew—that, like the people Israel after the High Priest had performed the Yom Kippur sacrifices, I had been cleansed. I went home happy that night: everything would be okay.

As I recall, that lasted two or maybe three weeks.

The next year, feeling even guiltier, I made the same supplication on Yom Kippur. And the year after that. And the year after that. I prayed earnestly for God to forgive me, to take it away, to make me normal, just like everyone else. When I grew older, and was beginning therapy in earnest, one of the questions I was asked was “Why do you believe you are transgender?” When I was younger, I believed it was because God had made an honest mistake. But as I got older and somewhat more theologically sophisticated sophomoric, I believed it was some kind of test, the purpose of which I could only guess at, and I wasn’t sure whether it was benevolently or malevolently intended. However, every time I prayed for God to “take the transgender away,” it only got stronger, and I ended up feeling, over and over again, miserable and worthless, like I’d failed the test.

I now know something I didn’t at the time: that many other people—trans, queer, both—have prayed that very same prayer alongside me. I was never alone; I always had company. I was not the first, and I will not be the last.

And every time I prayed it, it was an earnest, genuine prayer. But I discovered another prayer, a cry from my soul, that is even deeper, even more earnest and genuine. It took me long enough, but I finally heard it calling, from my kol d’mamah dakah, the “still small voice” within me.

The rabbis teach that all the rituals of confession, all the prayers for forgiveness, all the external trappings of Yom Kippur can only serve to atone for sins that are between a human being and God. Yom Kippur, they teach, does not bring atonement for sins one person commits against another, until the person who did wrong seeks forgiveness from the person who was wronged. This is one of the fundamental lessons of repentance and forgiveness in Judaism. The Hebrew word for “repentance” is teshuvah, which means, among other things, “returning.” The time between the start of the year on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur is called the Ten Days for teshuvah, for turning and returning inward, for the rediscovery of our selves. Yom Kippur asks us to return to the truth about ourselves; not to hide from it. It asks us to be genuine with ourselves; when we deceive ourselves, we cannot forgive ourselves.

I want to ask my younger self to forgive herself for not being perfect, for wronging herself by denying her inner nature, her truth, for failing to heed the kol d’mamah dakah within her. I want to reassure her that everything will be okay, that God doesn’t hate her, that she will eventually find and build a loving, accepting, and affirming community. I want to seek her pardon for the years of denials, purges, secrets, half-measures, traumas, deceptions, and lies I will inflict on her future self.

But the temporal continuum only works in one direction for us mere mortals, which means this exercise is doomed to failure. I cannot literally commit teshuvah by going back in time; I shall have to content myself with a metaphorical teshuvah. But I trust the kol d’mamah dakah within me, which tells me that this teshuvah must be more genuine than any other I have ever professed to make. I have to be willing to forgive my past self for not knowing that things would change, and both my past and present selves for being so hard on themselves, for demanding such perfection, for not giving themselves permission to fail. And I can try to return the courtesy to my future self: to give her permission to screw up, to fail, to commit wrongdoings and to learn from them. It’s a small comfort, but it helps.

A very wise friend of mine told me that beating myself up, as so many trans people do, for not having transitioned earlier is pointless. Whatever happened in the past, she pointed out, whatever decisions I made, were necessary at that time, because they kept me alive and got me to where I am now. When I introduced my blog (with this very point!) as “my record of surviving,“ I was not speaking metaphorically. And I am learning that part of survival—more than simple survival, actually; part of living—is having the ability to forgive myself.

So this is my Yom Kippur prayer this year. May I learn to accept and embrace the person I am, even if I do not know who she is yet. May I have the strength and the courage to forgive myself for the wrongdoings that I have committed against myself in the past, or will commit against myself in the future. May my teshuvah be sincere, and may it bring me closer to knowledge of my own truth. May I learn to recognize and to listen to the kol d’mamah dakah within me, and may I write my own Book of Life in that voice this year. May I love myself, may I remember that I am loved, and may I be at peace. Kein yehi ratzon—may this be so.

Adonai

Pronounced: ah-doe-NYE, Origin: Hebrew, a name for God.

Rosh Hashanah

Pronounced: roshe hah-SHAH-nah, also roshe ha-shah-NAH, Origin: Hebrew, the Jewish new year.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

Yom Kippur

Pronounced: yohm KIPP-er, also yohm kee-PORE, Origin: Hebrew, The Day of Atonement, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar and, with Rosh Hashanah, one of the High Holidays.