How did the sages view women?

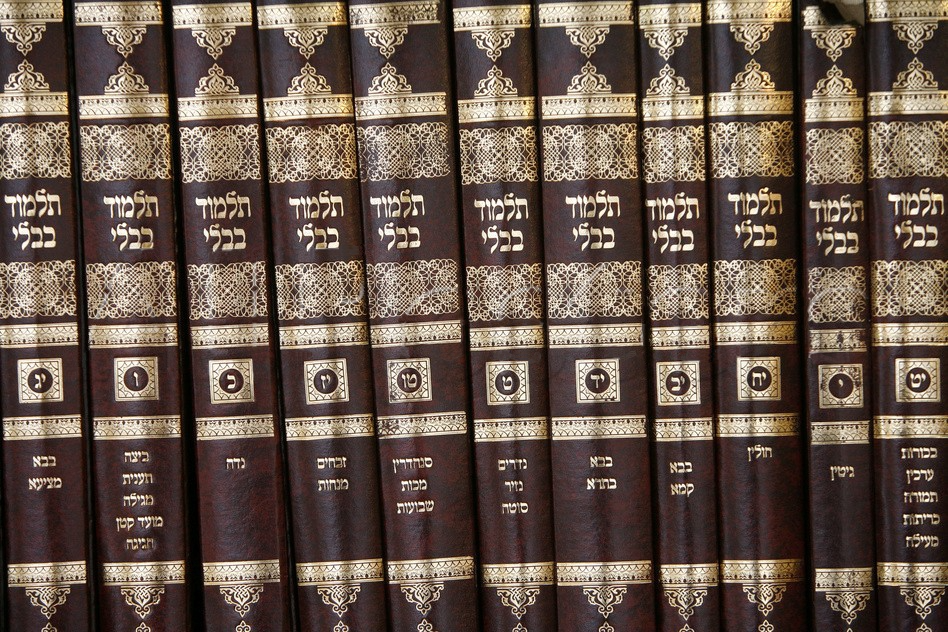

Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 62a expresses the basic rabbinic conviction that “women are a separate people.”

Despite the egalitarian vision of human creation found in the first chapter of Genesis, in which both male and female appear to share equally in the divine image, Rabbinic tradition is far more comfortable with the view of Genesis 2:4ff., that women are a secondary conception, unalterably other from men and at a further remove from the divine.

This certainty of woman’s ancillary place in the scheme of things permeates rabbinic thinking, and the male sages who produced rabbinic literature accordingly apportioned separate spheres and separate responsibilities to women and men, making every effort to confine women and their activities to the private realms of the family and its particular concerns.

Women in the Public Sphere

These obligations included economic activities that would benefit the household, so that undertaking business transactions with other private individuals was an expected part of a woman’s domestic role. Women also participated in the economic life of the marketplace, worked in a number of productive enterprises, trades, and crafts, brought claims to the courtroom, met in gatherings with other women, and attended social events.

But whatever women did in public, they did as private individuals. Not only by custom but as a result of detailed legislation, women were excluded from significant participation in most of rabbinic society’s communal and power‑conferring public activities. Since these endeavors had mostly to do with participation in religious service, communal study of religious texts, and the execution of judgments under Jewish law, women were simultaneously isolated from access to public authority and power and from the communal spiritual and intellectual sustenance available to men. […]

Women and Family Life

As long as women satisfied male expectations in their assigned roles, they were revered and honored for enhancing the lives of their families and particularly for enabling their male relatives to fulfill their religious obligations.

As [the Babylonian Talmud, or BT, in] Berakhot 17a relates, women earn merit “by sending their children to learn in the synagogue, and their husbands to study in the schools of the rabbis, and by waiting for their husbands until they return from the schools of the rabbis.”

This remains the case even as rabbinic jurisprudence goes beyond biblical precedents in its efforts to ameliorate some of the disadvantages and hardships women faced as a consequence of biblical legislation, devoting particular attention to extending special new protections to women in such areas as the formulation of marriage contracts that provided financial support in the event of divorce or widowhood and, in specific circumstances, in allowing a woman to petition a rabbinic tribunal to compel her husband to divorce her. […]

Negative Traits Ascribed to Women

Woman’s otherness and less desirable status are assumed throughout the rabbinic literature. While women are credited with more compassion and concern for the unfortunate than men, perhaps as a result of their nurturing roles, they also are linked with witchcraft (Mishnah Avot 2:7; Jerusalem Talmud Kiddushin 4, 66b), foolishness (BT Shabbat 33b), dishonesty (Genesis Rabbah 18:2), and licentiousness (Mishnah Sotah 3:4, and BT Ketubot 65a), among a number of other inherent negative qualities (Genesis Rabbah 45:5).

Sometimes the secondary and inferior creation of women is cited as explaining their disagreeable traits (Genesis Rabbah 18:2); elsewhere Eve’s culpability in introducing death into the world accounts for women’s disabilities in comparison to male advantages (Genesis Rabbah 17:8). Aggadic [narrative] exegeses of independent biblical women tend to criticize their pride and presumption. Thus, the biblical judge Deborah is likened to a wasp, and the prophetess Huldah to a weasel (BT Megillah 14b); other biblical heroines are similarly disparaged, and women who display unusual sagacity often meet early deaths (BT Ketubot 23a).

Women do utter words of wisdom in rabbinic stories, but generally such stories either confirm a rabbinic belief about women’s character, such as women’s higher degree of compassion for others (BT Avodah Zarah 18a; BT Ketubot 104a), or deliver a rebuke to a man in need of chastisement (BT Eruvin 53b; BT Sanhedrin 39a).

The Case of Beruriah

Both qualities are present in traditions about Beruriah, the wife of the second century C.E. rabbi, Meir, known for her unusual learning and quick wit (BT Pesahim 62b, BT Erubin 53b‑54a). Yet Beruriah’s scholarship was a problem for rabbinic culture, and in later rabbinic tradition she is shown to reap the tragic consequences of the “lightmindedness” inherent in woman’s makeup: in his commentary on BT Avodah Zarah 18b, Rashi ([the pre-eminent] eleventh-century [Bible and Talmud commentator]) relates that Beruriah was seduced by one of her husband’s students and subsequently committed suicide.

Contemporary scholars have shown that the scholarly Beruriah is a literary construct with little historical reality, yet they agree that the traditions about her articulate profound disquiet about the role of women in the rabbinic enterprise.

Rachel Adler suggests that Beruriah’s story expresses rabbinic ambivalence about the possible place of a woman in their wholly male scholarly world, in which her sexuality was bound to be a source of havoc. Daniel Boyarin writes that for the amoraic sages of the Babylonian Talmud, Beruriah serves as proof of “R. Eliezer’s statement that ‘anyone who teaches his daughter Torah, teaches her lasciviousness’ (Mishnah Sotah 3:4);” in rabbinic culture, he writes, “The Torah and the wife are structural allomorphs and separated realms…both normatively to be highly valued but also to be kept separate.” […]

The Problem of Female Sexuality

Women constitute an additional source of danger in rabbinic thinking, because their sexual appeal to men can lead to social disruption.

A significant argument for excluding women from synagogue participation rests on the talmudic statement, “The voice of a woman is indecent” (BT Berakhot 24a). This idea emerges from a ruling that a man may not recite the Shema while he hears a woman singing, since her voice might divert his concentration from the prayer. Extrapolating from hearing to seeing, rabbinic prohibitions on male/female contact in worship eventually led to a physical barrier (mehitzah) between men and women in the synagogue, to preserve men from sexual distraction during prayer.

Indeed, viewing women always as a sexual temptation, rabbinic Judaism overall advises extremely limited contact between men and women who are not married to each other. This is to prevent inappropriate sexual contact, whether adulterous, incestuous, or simply outside of a married relationship.

The Autonomy and Ownership of Women

In her detailed study of the legal status of women in the Mishnah, Judith Wegner points out the role of women’s sexuality. She demonstrates that in all matters that affect a man’s ownership of her sexuality-‑whether as minor daughter, wife, or levirate widow–woman is presented as belonging to a man. In nonsexual contexts, by contrast, the wife is endowed with a high degree of personhood. Her legal rights as a property holder are protected, and she is assigned rights and privileges that are denied even to non‑Israelite males.

Notably, mishnaic legislation always treats as an independent “person” a woman on whose sexuality no man has a legal claim. Such an autonomous woman–who might be an emancipated daughter of full age, a divorcee, or a widow–may arrange her own marriage, is legally liable for any vows she may make, and may litigate in court. Free from male authority, she has control over her personal life and is treated as an independent agent.

Wegner emphasizes, however, that while the autonomous woman has some latitude in the private domain of relationships between individuals, mishnaic rules governing women’s relationship to the public domain tell quite a different story. Here, all women are systematically excluded from the religiously prestigious male domains of communal leadership, collaborative study, and public prayer.

Excerpted and reprinted with permission of The Continuum International Publishing Group from The Encyclopedia of Judaism, edited by Jacob Neusner, Alan Avery-Peck, and William Scott Green.

Avot

Pronounced: ah-VOTE, Origin: Hebrew, fathers or parents, usually refering to the biblical Patriarchs.

Shabbat

Pronounced: shuh-BAHT or shah-BAHT, Origin: Hebrew, the Sabbath, from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.