Purim opens on a somber note. Haman is identified as the descendant of Amalek, whose people attacked Israel in the desert, the symbol of cruelty to the weak. Before celebrating the defeat of the wicked, one must remember that God (as well as God’s people) has a war with the Amalekites and will not be at ease until the Amalekites are blotted out. Jews are pledged to work for the end of oppression of the weak everywhere; a temporary, partial victory should not blind one to the persistence of evil in the world.

On the Sabbath before Purim, the portion of the Torah dealing with Amalek is read. This day is called Shabbat Zachor, the Sabbath of Remembrance. It is a special mitzvah [commandment] of the Torah to hear the reading and thus remember.

Zachor [remembrance] is a mitzvah that has made modern Jews uncomfortable. The natural desire to forget and be happy collides with the ongoing pain of memory and analysis. When asked why President Ronald Reagan in 1985 initially declined to visit the Dachau concentration camp, a presidential aide explained that the President was an “up” type of person and did not like to “grovel in a grisly thing.”

Modern people who are future-oriented stress the need to forgive. They argue that there will be no reconciliation as long as the memories of the cruelties and atrocities of the past are preserved and thrown in the face of those involved. “Forget and forgive” becomes the slogan. This argument can even take the form of an attack on the victims for keeping the memory alive. In May 1985, a storm of opposition arose against President Reagan’s visit to the Bitburg, Germany, military cemetery because the ceremony involved paying homage and laying a wreath in a cemetery with graves of SS Soldiers. During the uproar, one German parliamentarian attacked the Jews for their unchristian-like refusal to forget the past!

Avoiding Past Mistakes

The primary lesson of Parashat Zachor [the special section of the Torah read on that Shabbat] is that true reconciliation comes through repentance and remembrance. Confronting the evils of the past is the most powerful generator of moral cleansing and fundamental reconciliation. Repentance is the key to overcoming the evils of the past. When people recognize injustice they can correct the wrongdoing and the conditions that lead to it. In the 20th century, repentance has liberated many Christians from past stereotyping and hatred of Jews, thus beginning to transform Christianity into a gospel of love, which it seeks to be.

Remembrance is the key to preventing recurrence. Goaded by the memory of the failures of the 1930s, the indifference toward Jewish refugees, the American government in 1979 organized a worldwide absorption program for two million boat people. Goaded by memory, America’s Jews and Israel responded to the crisis of Soviet Jewry and, belatedly, of Ethiopian Jewry.

Naivete and amnesia always favor the aggressors, the Amalekites in particular. The Amalekites wanted to wipe out an entire people, memory and all; amnesia completes that undone job. Ingenuousness leads to lowering the guard, which encourages attempts at repetition. One of the classic evasions undergirding naivete is the claim that Amalek is long since gone. Only “primitive” people are so cruel, only madmen or people controlled by a Svengali/Hitler type would do such terrible things. The mitzvah of Zachor is a stern reminder that Amalek lives and must be fought.

Through Zachor, one learns to distinguish types and levels of evil. Not every evil is Amalek, but the ultimate evil must be destroyed. King Saul had a chance to wipe out Amalek, but in pity he spared Agag, the king. Centuries later, Haman the Agagite, the descendant of Agag, plotted the mass extermination of Jews (Esther 3:1). Says the Talmud, “Whoever is compassionate to those who deserve cruelty ends up being cruel to those who deserve compassion” (Midrash Tanhuma Metzora, Jerusalem Eshkol, 1971), section 1).

The Fast of Esther

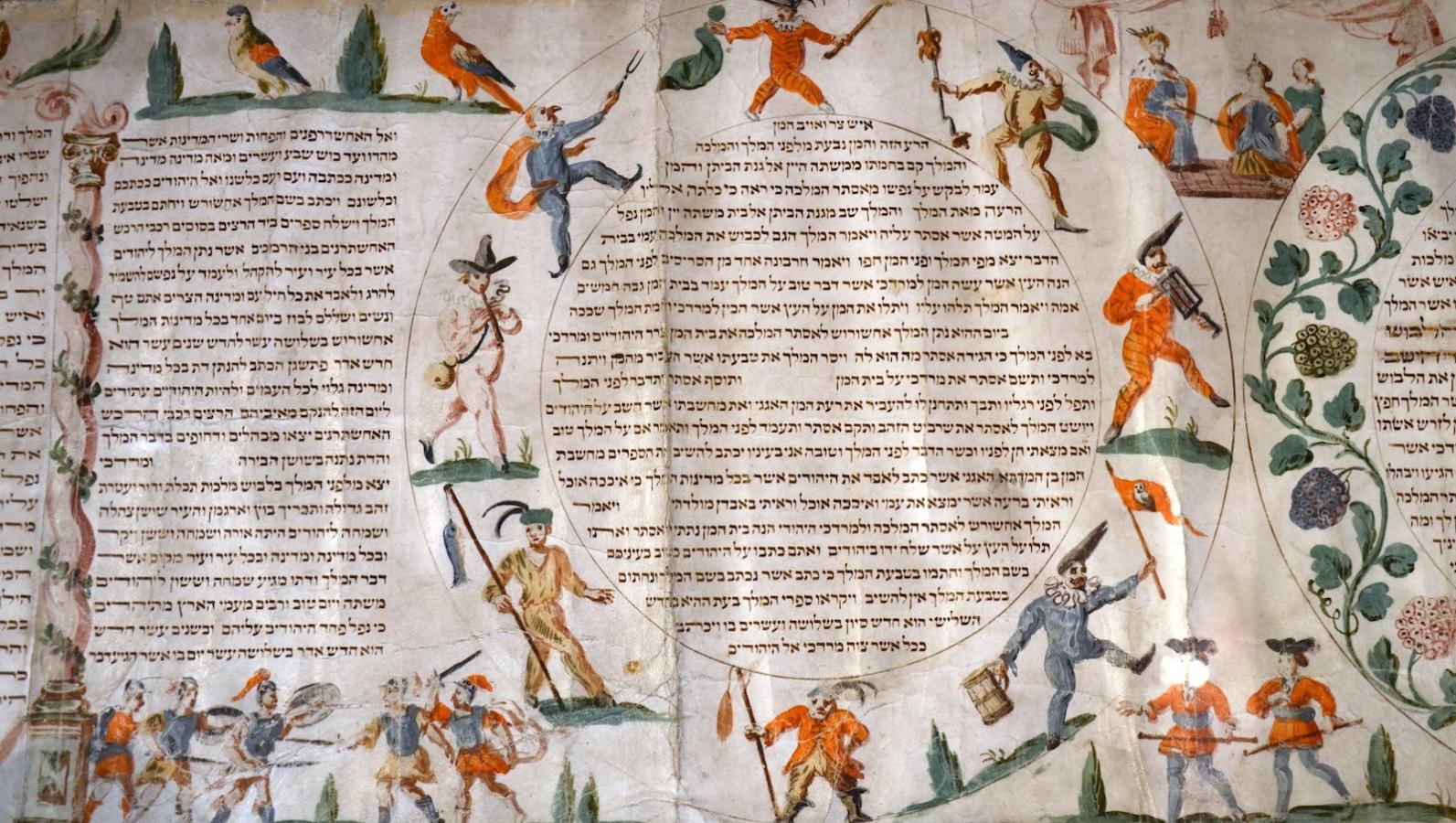

Having recalled the forces of evil, the Jew now proceeds to recall the bitter memory of the helplessness and the terror of innocents suddenly condemned to death without rhyme or reason. This mood is actually part of the story of the Megillah [Scroll of Esther], but it would be almost impossible to capture in the midst of Purim exultation. Therefore, the day before Purim was established in the rabbinic period as a fast day, the fast of Esther.

Again, the Rabbis show the strong halakhic [Jewish legal] preference for dialectical experiences that reinforce one another. Here, fasting is just as important to holiness as feasting. The fast day of Esther corrects the excesses in Purim. To the sense of triumph and mastery over fate celebrated on Purim, the fast of Esther responds with a reminder of the powerlessness that preceded the day. Before the merrymaking and dulling of one’s senses through drunkenness begin, the fast day offers the introspection and meditations of penitential prayers and Avinu Malkeinu (our Father, our King, we have sinned before You). As against the sense of triumph over enemies celebrated by booing Haman (it could easily turn into arrogance), the fast of Esther holds up the teaching of vulnerability.

Reprinted with permission of the author from The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays

mitzvah

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Purim

Pronounced: PUR-im, the Feast of Lots, Origin: Hebrew, a joyous holiday that recounts the saving of the Jews from a threatened massacre during the Persian period.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.