Commentary on Parashat Toldot, Genesis 25:19 - 28:9

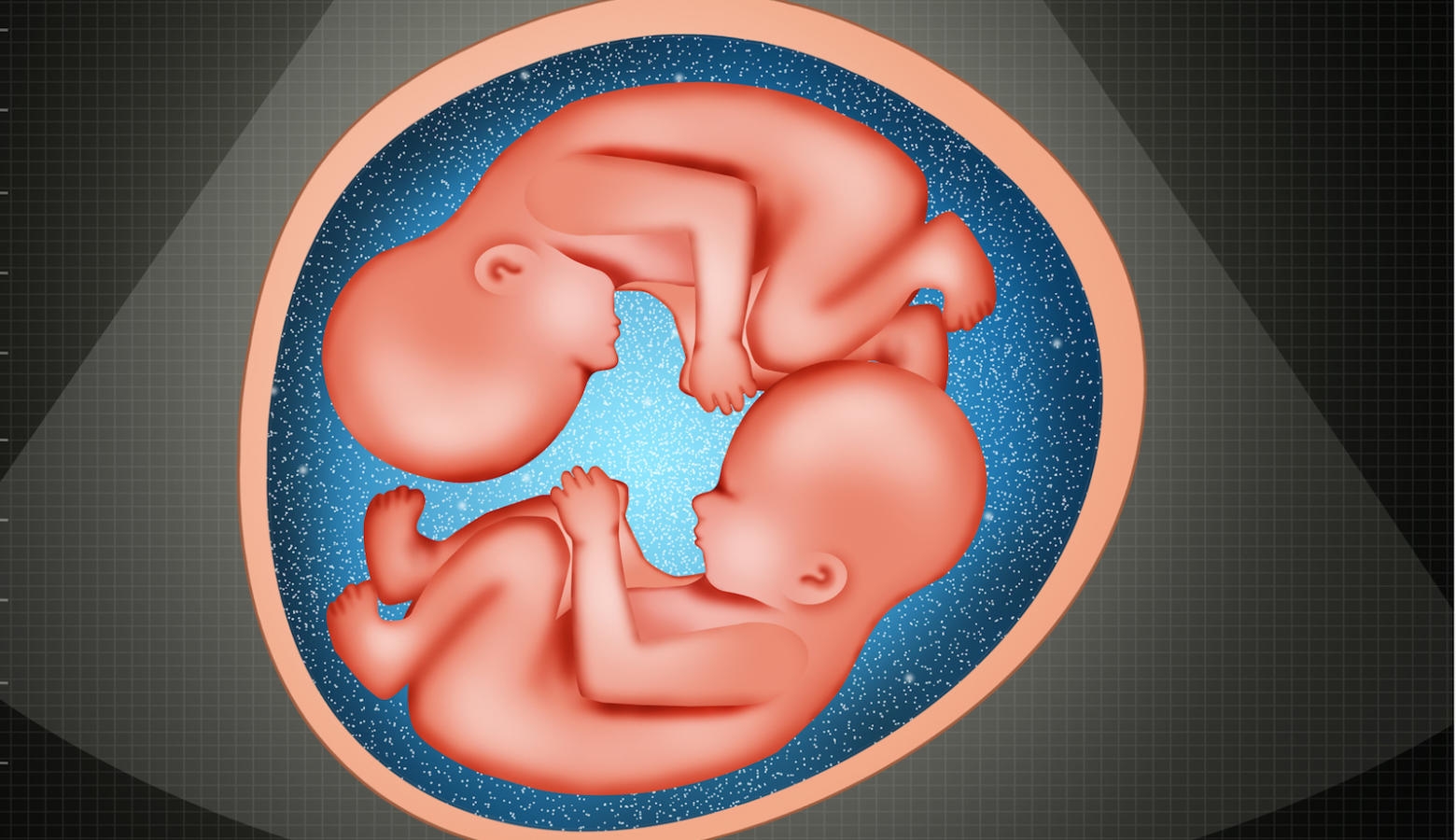

Toldot is the only portion in the Torah that puts Isaac at the center of the action. Yet it jumps right into the next generation. The portion begins with the birth of Isaac and Rebecca’s twin sons Jacob and Esau. Like Sarah before her, Rebecca is deemed to be barren, but then miraculously gives birth later in life. It’s a difficult pregnancy. She “inquires of the Eternal” and finds out that she’s carrying twins.

The first child emerges all red and hairy, and is named Esau. The second boy comes out holding onto his brother’s heel. He is named Jacob, from the Hebrew root meaning “heel.” When they grow up, Esau becomes a hunter, “a man of the field.” Jacob is described as a “mild man,” who preferred to remain back in the camp. Isaac favored Esau. Rebecca prefers Jacob.

This context of parental favoritism and sibling rivalry serves as the backdrop for the complex relations and tragic events that follow. Jacob takes advantage of a weakened Esau and gets him to sell his birthright for a bowl of lentils.

Later, famine forces the family to leave Canaan and travel to Gerar. Isaac and Rebecca repeat (third time — second with Abimelech) the wife/sister confusion of Abraham and Sarah, and then they must deal with some issues of water rights left over from Abraham. Now wealthy, they end up settling in Beersheva, where God appears to Isaac, and Abimelech, the King of Gerar, establishes a treaty with him. This section ends with the news that Esau, at the age of forty, married two Hittite women. They are described as being a “source of bitterness to Isaac and Rebecca.”

The story continues some time later when Isaac is old and blind. Fearing the end of his days is near, he called his oldest son Esau to receive his final blessing. But first he asks Esau to hunt and prepare him some game. Rebecca overhears this request and, while Esau is out is the field, she prepares the food and dresses Jacob like his brother and sends him in to receive the special blessing in Esau’s place. Esau comes in later, and it is then that he and his father Isaac realize they have been tricked. Isaac offers Esau a secondary blessing, but it is not enough. Having now been tricked out of both his birthright and his blessing, Esau declares his hatred for Jacob and his intention to kill him. Rebecca hears of the plot and arranges for Jacob to flee to Haran, to the home of her brother Laban.

In Focus

But the children struggled in her womb, and she said, “If so, why do I exist?” She went to inquire of the Eternal.” (Genesis 25:22)

Pshat

To be honest, the Pshat (the simple meaning of the text) is not so clear. Isaac pleads with God to allow Rebecca to conceive. God responds positively and she does become pregnant. Unfortunately, it proves to be a difficult pregnancy, with what turns out to be twins struggling in her womb. Despondent, Rebecca cries out in anguish. However, the words of her exclamation, as recorded, are ambiguous. She then goes herself to seek an explanation from God.

Drash

I don’t think there is a woman in the world who has been pregnant (especially with twins) who cannot relate to Rebecca’s discomfort and anguish. And for her to cry out in an incomprehensible manner, that too is understandable. Bearing children is tough work. However, the Torah is not so comfortable with passages that seem to not make sense. Nothing in Torah is superfluous or redundant. Therefore, we need to try and find meaning in Rebecca’s words.

Im keyn, lammah zeh ‘anokhi (Genesis 25:22) is usually translated as something like, “If so, why do I exist?” But, as Nahum Sarna notes in JPS Torah Commentary: Genesis, the Hebrew phrase is actually an incomplete sentence, literally meaning something like, “If so, why then am/do I…” The phrase is dramatic and powerful in its incompleteness. One can almost imagine a twinge of severe pain doubling Rebecca over in mid-exclamation, as if to emphasize her distress.

But we need to remember that Rebecca’s pregnancy is the result of a divine act. Repeating the motif of the barren wife of a patriarch, Rebecca remains childless twenty years after her marriage to Isaac. But, unlike his father Abraham, it was Isaac himself who acts this time, praying to God to intervene

Isaac’s act of faith is rewarded with fertility. But, despite the fact that this pregnancy is the result of God’s response, it is not to be easy for Rebecca. Rebecca’s desperate cry then becomes a statement of faith in of itself. But what do these words mean? Could she possibly be questioning the miraculous gift that God has given her?

Rashi expands Rebecca’s words to try and explain their meaning. He explains the phrase to mean, “If the pain of pregnancy be so great, why is it that I longed and prayed to be pregnant?” In this reading, she seems to blame not God but her own naiveté for getting her into this uncomfortable situation. It is a “Be careful of what you ask, because you just might get it” type of situation.

Ibn Ezra gives a different explanation. He suggests (following a midrash) that Rebecca went around to all the women of the community to ask if they had experienced such pain in pregnancy. They all answered, “No.” Realizing that her pregnancy is different, Rebecca cries out, seeking to know why her experience is unusual.

This is supported by the following inquiry she makes of God. She simply sought an explanation of what was going on in her body, and she came to realize that only God, the One who blessed her with this miraculous pregnancy, could provide the answer.

But Ramban (Moses Ben Nachman) describes Rebekah’s anguish as reflecting a much more existential anxiety. He translates Rebekah’s words as a challenge to her very existence in the world: “If it be so, why do I live?”

Like Moses who exhorts God to let him die rather then put up further with the complaints of the Children of Israel (Numbers 11:15) and Job whose unending despair compels him to exclaim, “I should have been as though I had not been!” (Job 10:19), Rebecca reaches the point where she simply can no longer cope. She questions the very purpose of her existence. And, in doing so, she questions God’s plan for her as well. She recognizes that her current situation is a result of divine providence. What she doesn’t understand is why. And so she decides to go straight to the source. She goes to inquire of God.

A crisis of faith is always a challenge for the person whose faith has been rocked. For our biblical ancestors, expressing doubt in God could often result in dire consequences, leading them to question the very purpose of their being. In a world where the secular and the spiritual were inseparable, physical death seemed like a viable alternative to spiritual angst.

Today, it is not the death of body we fear when we struggle with faith, but the threat of spiritual death is very real. And it is here that we can follow the model of Rebecca who seeks solace by turning to God.

The text uses the word L’drosh, “to inquire,” but more literally “to challenge” or “to struggle” with God to discover her fate. Rather than turning away from God, Rebecca turns to God, but to challenge God; to find meaning out of her anguish. Rebecca does not turn away, asking, “Why is God doing this to me?'” but rather she turns to God, asking, “What is the meaning of this experience?” Though her words be jumbled, her actions speak louder. It is the authentic Jewish act: to struggle with God.

Davar Aher (Another Thing)

What was the nature of Jacob and Esau’s in utero struggle? The midrash (Genesis Rabbah 63:6) indicates the boys were very precocious:

And The Children Struggled Together Within Her. They sought to run within her. When she [Rebekah] stood near synagogues or schools, Jacob struggled to come out; hence it is written, Before I formed thee in the belly I knew thee (Jeremiah 1:5). While when she passed idolatrous temples, Esau eagerly struggled to come out; hence it is written, The wicked are estranged from the womb (Psalm 58:4).

Provided by KOLEL–The Adult Centre for Liberal Jewish Learning, which is affiliated with Canada’s Reform movement.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.