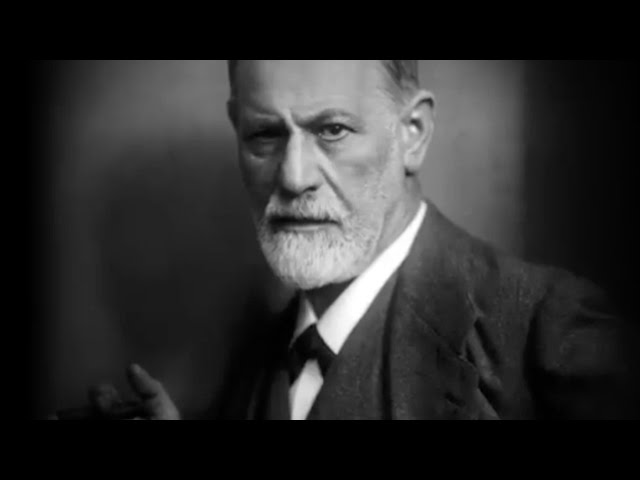

In his book, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, Sigmund Freud suggested that many Jewish jokes point to the ability of the Jewish people to (a) engage in a thorough self-criticism of themselves, (b) advocate a democratic way of life, (c) emphasize the moral and social principles the Jewish religion, (d) criticize the excessive requirements of it, and (e) reflect on the misery of many Jewish communities.

Freud, who wrote this book some hundred years ago, was actually paying homage to the capacity of the Jewish people to overcome the oppressive social conditions that had been imposed upon them and their ability to transcend them by laughing at them.

Masochism?

Some non-Jewish psychiatrists – -even disciples of Freud — seem to have had some difficulty in understanding the gist of Jewish wit and have been particularly critical. Their preconceived ideas about the Jews may have had a certain influence in their judgment. Dr. Edmund Bergier, in a book he published in 1956, Laughter and the Sense of Humor, expresses the view that a definite tendency to “psychic masochism” is present in Jewish wit, and that certain external situations (discrimination, poverty, the lack of opportunity, and the bitterness of life in Eastern Europe) have predisposed Jews to a certain degree of masochism.

Dr. Martin Grotjahn, a disciple of Theodor Reik [who himself was a disciple of Freud], published a book on the subject in 1960, titled Psychoanalysis and the Jewish Joke, in which he advances the opinion that the witticisms of Jews often start with an aggressive tendency, a shocking thought, or an offensive statement in a disguised form. The release of aggression is sudden, and the hostility or aggressiveness manifests itself in a masochistic way–that is, turned against the Jew himself.

Pseudo-Masochism

These notions were corrected, however, by Reik himself, who remarked that the masochistic aspect of the Jewish joke may not be authentic. It is only pseudo-masochistic because the masochism of Jewish wit is only a “mask” that does not show the face behind it. For the ultimate aim of this display is the unconscious wish to win the approval–or even the admiration–of the audience, and to regain one’s dignity. It is as if the jester were saying, “See how full of weaknesses and failings I am. Therefore you must recognize my humanity, forgive me, and love me again.”

Reik justified his conclusion by stating that, contrary to the clinically diagnosed masochist, the Jew does not derive gratification from this type of behavior, as does the authentic masochist. Indeed, the Jew makes fun of himself, but he does not come out humiliated or dirty. His self-humiliation is perhaps only a measure of self-defense, which may protect him against greater dangers. It is thus a kind of sacrifice made in order to survive. Jewish jokes are therefore only pseudo-masochistic and not really masochistic.

Reik went on to suggest the possibility of the coexistence of masochistic humility and provocative insolence. As an example of this attitude, he referred to a letter written by the German Jewish poet and writer Heinrich Heine, who had converted to Christianity in hope of being accepted by Western society, in which Heine a few months before his death says to his brother Max, “Our forefathers were brave people; they humbled themselves before God and were stubborn and fearless towards the worldly powers. I, on the contrary, challenged Heaven with impudence and was humble and servile towards people, and now, I lie on the ground, like a worm that has been crushed under a foot.”

That does not mean, of course, that we do not have some true masochists or paranoid personalities among us from time to time, as the saying goes: “Just because you are paranoid, does not mean that they are not out to get you.”

What Grotjahn meant by an aggression turned against itself might be expressed in these words: “You don’t need to attack us. We can do that ourselves and even better. We can take it. We know our weaknesses, and in a way, we are proud of them.” Jewish jokes, he writes, contain a kind of resignation and occasionally a stubborn pride. They seem to say: “This is the way we are and will be as long as we exist.”

Two Sides to Every Story

For Freud and for Reik, the truth seemed at once simpler and more complex. There is often a kind of oscillation between a pseudo-masochistic self-humiliation and a sense of paranoid superiority in Jewish humor. Thus, there are two sides to every Jewish story.

No one will deny that there is a high degree of resiliency and courage that is displayed in many Jewish stories, and that has served as a kind of defense-mechanism enabling Jews to confront adversity. The fact that Jews are capable of making merciless fun of the shortcomings of their own people is a positive trait, not a negative one, as some anti-Semites have tried to construe it. Self-criticism, and even self-sarcasm, are part of the thought process of the individual who is committed to intellectual and moral integrity.

The world has changed considerably in the years since Reik wrote his book, and we may say, today, that the universal character of Jewish wit has come to be enjoyed by many–Jews and non-Jews alike. Some of the finest humorists on the American scene are Jewish, and many gentiles have learned to enjoy and appreciate a good Jewish joke

Woody Allen is a case in point He may be ambivalent about his Jewishness, but he has certainly not rejected the Jewish tradition of humor He has been quoted as saying, “I have frequently been accused of being a self-hating Jew, and while its true I hate myself, it’s not because I am Jewish.”

That’s Jewish humor in full flower.

This article is the last in a four-part series on the characteristics of Jewish humor. The series originally appeared as a single article in Midstream magazine, which was anthologized in Best Jewish Writing 2003. It is reprinted with permission.