Commentary on Parashat Noach, Genesis 6:9 - 11:32

“Don’t put all your eggs in one basket,” goes a well known bit of folk wisdom. If the basket should fall, you’ll lose everything at once. While this may be plain common sense for the weekend shopper, we seem to have a harder time following this principle when it comes to preserving diversity among the world’s living creatures.

To take just one example, 90 percent of all eggs sold in the United States are laid by one breed of hen, the White Leghorn. What would happen to our egg supply if some disease struck this breed?

Rice in India

Or consider the fact that India had 30,000 varieties of rice just 50 years ago. Today it depends upon just 10 strains, most of which are not native to India, but are hybrid seeds, engineered to produce higher yields in shorter growing seasons. Farmers who switch to these new varieties often abandon more genetically diverse local types, many of which then become extinct. The result–a radical narrowing of the agricultural gene pool–places the world food supply at risk. It’s the global equivalent of putting all our eggs in one basket.

Why do we need so many different kinds of rice in the first place? In short, because genetic variety holds out the best hope for species survival. In the 1970s, a virus swept through rice paddies from India to Indonesia. Fortunately, seed banks contained samples of enough varieties to produce a solution. After testing 6,237 kinds of rice for resistance to the virus, only one species, an Indian strain called Oryza nivara, contained genes that could withstand the virus. It was cross-bred with a commonly cultivated variety, and the hybrid seed is now grown across Asia.

So are seed banks the solution to our problem? While seed banks represent an important strategy for preserving nature’s genetic bounty, many types of seeds cannot be stored by conventional means. Furthermore, only a tiny fraction of plant species is covered by seed-bank inventories, and it is far beyond the resources of such programs to collect and maintain the thousands of endangered varieties. Most important, while seeds from certain species can be stored, their “partners in nature”– insects that pollinate it, fungi that bring it nutrients, etc–cannot all be stored at the same time. In the absence of their symbiotic partners, many seed-bank species do not survive when replanted.

Preserving Natural Eco-Systems

Today, scientists suggest that the best way to preserve the world’s biodiversity is to preserve as many as possible of its natural eco-systems. Especially important are those such as rain forests, which contain a large concentration of plant and animal species. By protecting the global environment, and specifically by designating certain biological “hotspots” as inviolate preserves, we can slow the narrowing of the genetic flexibility that ensures life on Earth.

Rabbi Yehudah said in the name of Rav: “Everything that God created in the world has a purpose. Even things that a person may consider to be unnecessary have their place in creation.” (Bereshit Rabbah 10:8). We are witnessing and helping produce the most rapid decline of species diversity in the history of the earth, and yet we barely understand the place in creation of most of the world’s species, including those that have been lost to us through extinction. Researchers have recently discovered that the rosy periwinkle of Madagascar produces two alkaloids that cure most victims of two of the deadliest cancers: Hodgkin’s disease and acute lymphocytic leukemia. How many sources of healing have been lost to us forever through environmental neglect?

Reinforcing this midrashic awareness of the versatility of species, Judaism contains a legal proscription against wanton destruction of property and natural resources, known by its command form bal tashchit, “do not destroy.” This prohibition reflects the belief that human beings are temporary tenants on God’s earth (Leviticus 25:23), charged to till it for their needs, but also to tend it, that it may be saved for future generations. (Genesis 2:15)

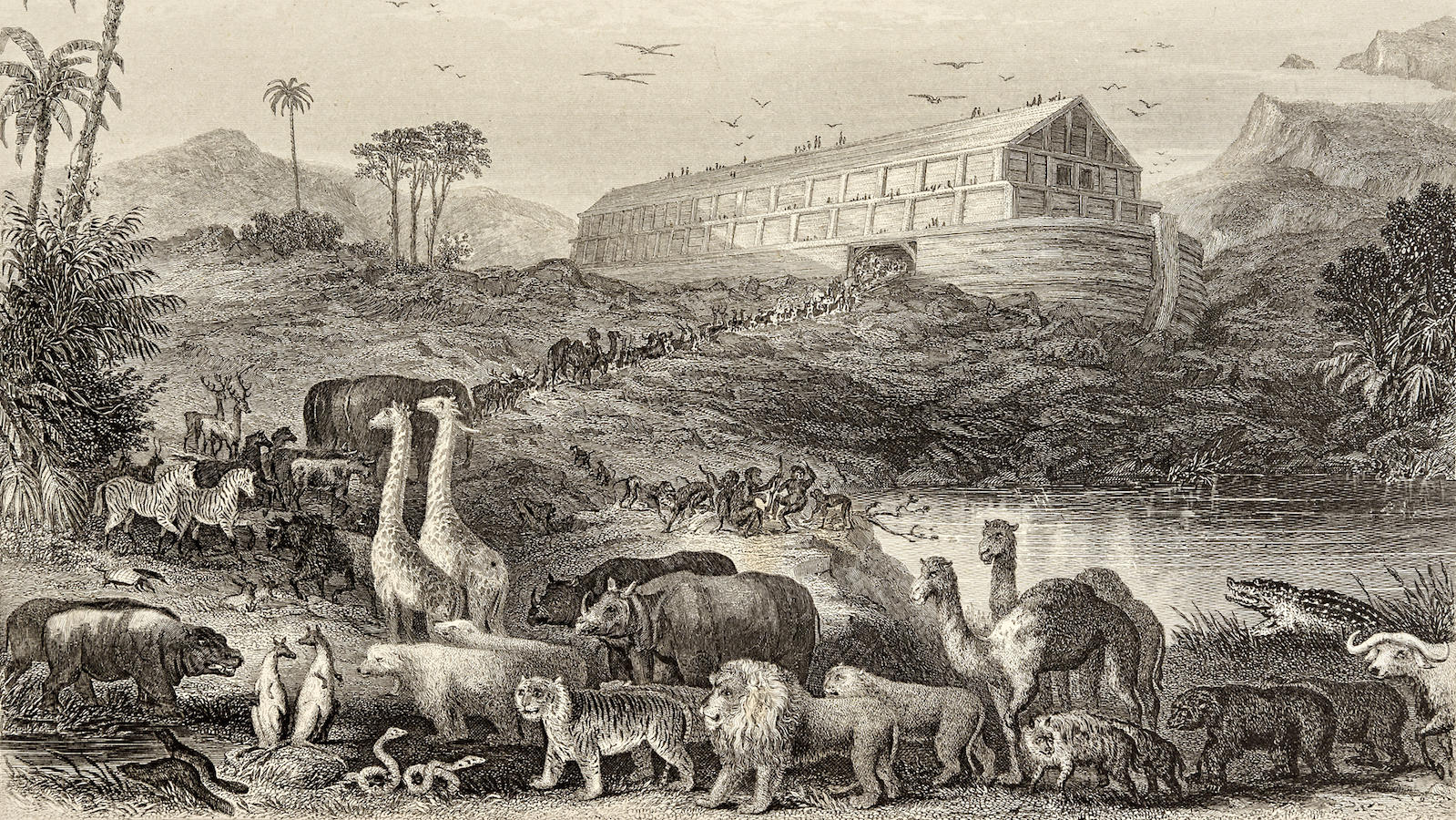

The Torah sounds the theme of conservation in this week’s reading as well, through its description of the careful preservation of every species on earth in Noah‘s ark, both the “clean” and the “unclean.” After the flood, God makes a covenant with Noah’s descendants and with “every living thing on earth” never again to destroy the world. (Genesis 9:8-10) Do we dare allow ourselves to proceed with that which God has foresworn?

Preserving biodiversity is an issue of planetary survival, but it is also–as we have seen–a theological issue. Nature’s stunning variety often invokes feelings of deep fascination and awe, attitudes closely associates with religious experience. Maintaining our capacity to appreciate such feelings–our capacity for wonder–may enable us to enlarge our sense of God’s presence in the world and to enhance our appreciation for the sidrei bereshit–the orders of creation. Conversely, by allowing creation to be diminished, we invariably diminish ourselves as well.

To find out more about the sources and scope of the crisis of biodiversity, as well as some possible solutions, I recommend these books: Diversity of Life by Edward O. Wilson (Harvard University Press, 1992) and The Rain Forest In Your Kitchen (Island Press, 1992).

Provided by SocialAction.com, an on-line Jewish magazine dedicated to pursuing justice, building community, and repairing the world.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.