On April 11, 1987, Primo Levi jumped to his death from the third-floor stairwell of the apartment building in which he had resided as a child, and to which he returned after the Holocaust.

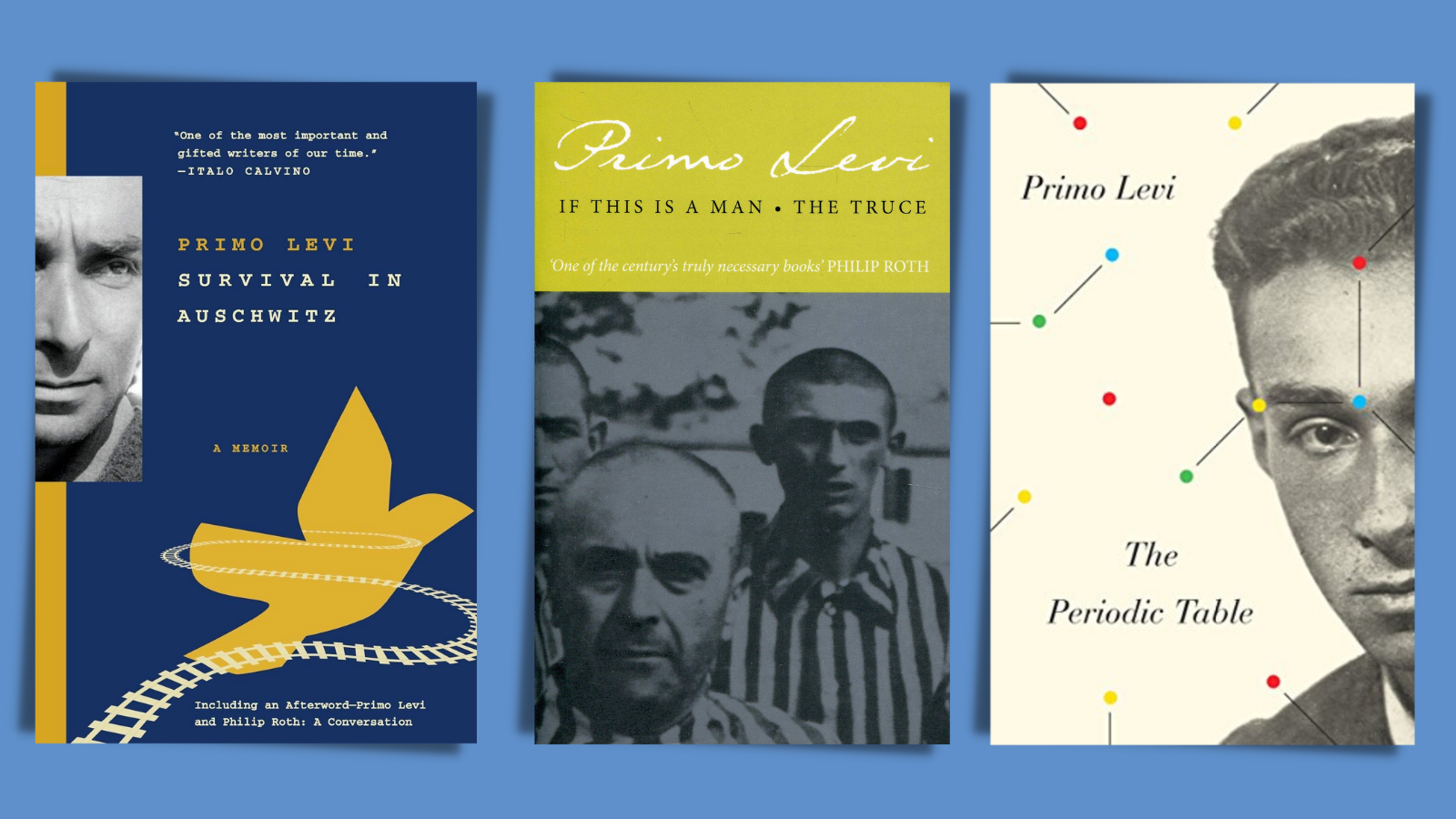

An Italian-Jewish chemist, poet, and author, Levi was renowned for his autobiographical accounts of his experiences during and immediately following World War II. His Survival in Auschwitz was one of the first autobiographical accounts of the Holocaust to be published, a mere three years after the end of the war. But it was in the decades that followed that Levi reached his greatest heights of public acceptance, and the greatest depths of his personal tragedy.

Levi’s suicide came as a shock to many readers. It flew in the face of the principles that Levi had stood for, and seemed to undermine his steadfast commitment to the value of perseverance, which he had stressed repeatedly in his writings as in his life. But close friends and peers were less surprised. Elie Wiesel, also a survivor of Auschwitz, said of Levi that he had in fact died “in Auschwitz, 40 years later.”

The Life of Levi

Primo Levi was born on July 31, 1919, in Turin, Italy. As a child, he was frail and sickly, and was mocked for his small frame and timid disposition. Though socially withdrawn, Levi excelled academically, and was among the last Jews to receive academic degrees before racial laws made it illegal for Jews to study in universities.

While his mother and sister hid during the Holocaust, Levi joined a partisan group. The group was infiltrated by fascists, and Levi was sent to a labor camp in Fossoli, Italy. Within a few weeks the entire camp was transferred to Auschwitz. Levi survived 11 months in Auschwitz and the 10-month journey home that followed. For the rest of his life, he would be consumed by these experiences.

A Nuanced Approach to Evil

As an author, Levi was admired as much for his close attention to detail as for his objective style, which was neither self-pitying nor self-aggrandizing. Levi’s writings took a nuanced approach to a subject that is almost always portrayed in strict terms of good and evil. He saw Auschwitz as a complex system in which the Nazis had devised a process of dehumanization that pitted victims against each other in an animalistic fight for survival. By oppressing their victims, writes Levi, the Nazis themselves became dehumanized, because to act inhumanely, as Levi explains, is to deny one’s own humanity. The Nazis, he wrote, sought “to annihilate us first as men in order to kill us more slowly afterwards.”

Similarly, Levi noticed even the smallest acts of kindness and compassion that took place in the camp against all reason. For him, these served as a testament to human dignity and the inherent ability to transcend the darkness of Auschwitz through acts that affirm essential humanity.

In an interview with Philip Roth in 1986, Levi said of himself:

I never stopped recording the world and people around me, so much that I still have an unbelievably detailed image of them. I had an intense wish to understand, I was constantly pervaded by a curiosity.

Tortured Body, Tortured Mind

Although he wrote prolifically about his wartime experiences, Levi was plagued by a fear of not being fully understood or believed. In Survival in Auschwitz (originally titled If This is a Man), Levi describes a recurring dream: he is at home, with his sister and many others. “They are all listening to me,” as he tells his story, but he soon notices that his “listeners do not follow” him, “they are completely indifferent….”

In Auschwitz, Levi worked as a chemist in the camp laboratory. There, he was better off than many of his fellow inmates, but he was not spared daily humiliations, minimal food rations, and beatings that were part and parcel of life as a Jewish slave laborer in the Nazi war machine. Levi credited his survival in large part to Lorenzo Perrone, an Italian civilian working in Auschwitz, who, over the course of the last few months of the war, managed to smuggle extra food to Levi every day. Perrone (for whom Levi named his son Renzo) also helped by writing a letter to Levi’s family in Italy and bringing him the reply, as well as supplying him with extra clothing to withstand the winter.

According to Levi, it wasn’t so much for the “material aid as for his having constantly reminded me, by his presence, by his natural and plain manner of being good, that there still existed a just world outside our own…a remote possibility of good, but for which it was worth surviving.” It was thanks to Lorenzo, Levi believed, “that I managed not to forget that I myself was a man.”

Perhaps the most poignant element of Survival in Auschwitz is the book’s final chapter, “The Story of Ten Days,” which recounts Levi’s experiences during the 10 days immediately following liberation. Because he was a patient in the camp infirmary when the camp was liberated, Levi was spared the final march of the inmates, during which the vast majority met their deaths.

Levi and his fellow sick inmates were left to fend for themselves. Against tremendous odds, Levi, with two of the more robust inmates, successfully found the means to feed themselves and their fellow bunkmates–a sack of potatoes was located just outside the camp gates and the snow that has not yet been contaminated was melted for washing and cooking.

With the exception of one fatally ill patient, all the inmates in Levi’s bunk survive these 10 days (five, however, ultimately succumb and die in the weeks following liberation). It is over the course of these 10 days that humanity, for Levi, returns to itself. An atmosphere of kindness and generosity towards fellow inmates, unthinkable under Nazi rule, suddenly pervades the bunk. Though harrowing, these 10 days mark the extraordinary transformation from imprisonment to freedom.

After Auschwitz

In October 1945, nearly 10 months after Auschwitz was liberated, Levi returned to his home, barely recognizable and visibly shaken by the traumas he had endured. Though his immediate family had survived the war, many of his friends were not as fortunate, and Levi was never able to shake the shadow of Auschwitz.

Levi published Survival in Auschwitz in 1948, three years after being liberated. He initially had difficulty finding a publisher, and when the book was finally released, sales were disappointing. Perhaps the world was not yet ready for such an honest account of what really happened in Auschwitz.

In 1958, when the book was rereleased, it gained international acclaim. Widely recognized as a literary masterpiece, Survival in Auschwitz offers readers an unsentimental portrayal of life in the death camp. A sequel, The Reawakening (or The Truce), soon followed, which related Levi’s experiences during his arduous 10-month journey home. Along the way, Levi encounters other Holocaust survivors, and a host of other characters, as he rediscovers the world.

Among Levi’s other books are The Periodic Table, a collection of short stories and personal anecdotes each tied to one of the chemical elements, and two novels, If Not Now, When? and The Monkey’s Wrench, as well as poems, essays and several collections of short stories.

The Perils of Fame

His final collection of reflections on the Holocaust, The Drowned and the Saved, was published posthumously. In it, Levi devotes a chapter to the Belgian philosopher and Auschwitz survivor, Jean Amery, who committed suicide in 1978. Levi quotes Amery, who said: ‘

He who has been tortured remains tortured…. He who has suffered torment can no longer find his place in the world. Faith in humanity — cracked by the first slap across the face, then demolished by torture — can never be recovered.

As with many survivors, Levi was consumed by a sense of guilt over having survived. The loss of faith in humanity, combined with the knowledge that “each of us [who survived] supplanted his neighbor and lives in his place…” may be what ultimately broke the man.