Commentary on Parashat Toldot, Genesis 25:19 - 28:9

The Torah portion of Toldot, which begins, “And these are the generations of Isaac, son of Abraham,”(Genesis 25:19) explores the meaning of human experience as the biblical story passes from one generation to the next. This reading tells the story of the birth of Jacob and Esau, their struggle for dominance over each other, and the ultimate selection of Jacob as the Patriarch through whom Jewish destiny will be transmitted. It also offers two distinct theories of history, indicating different approaches on how humans should conduct themselves in the face of momentous choices.

Defining Fate

The first theory of history is that human destiny is controlled by iron fate. We are born with a certain character, follow its dictates throughout our lives, and die without fundamentally changing our nature or, by extension, our effect on others. In this approach, our life course is set from the moment we enter this world.

The Torah conveys this view of history in its descriptions and explanations of names. The names that people are given at birth determine their character for their entire lives.

At the beginning of Toldot, we are told, “The first one emerged [from the womb] red, like a hairy mantle all over, so they named him Esau” (meaning “hairy” or “rough”) (Genesis 25:25). Indeed, as long as he lives, Esau will reaffirm this birth experience by acting wildly, roughly, ruled by passion and emotion.

His brother arrives hanging on to Esau’s heel (25:26), and so receives the name Jacob, derived from the Hebrew for “heel.” This name signals that Jacob’s whole life (and, according to Rabbinic interpretation, the lives of his descendants) will be consumed by a struggle for dominance over his brother.

Moreover, the name Jacob has another meaning, as Esau makes clear after his younger brother preceded him to Isaac and received his blessing. “That is why they called him Jacob,” Esau says in 27:36, meaning “sneak” (Everett Fox’s translation), charging that his brother has stolen both his birthright and his blessing. Esau is asserting here that Jacob must act like a sneak since that is the Hebrew root of his very name. In other words, Jacob’s actions mirror his personality that was destined since his naming at birth. In fact, later on in Genesis, the narrative will again highlight these qualities in Jacob’s confrontation with Laban.

The Torah states this fateful view of history most clearly in the first confrontation between Jacob and Esau. Esau, the man of the wild, arrives home to find the domesticated Jacob cooking a lentil stew whose color is red. The Torah relates Esau’s demand as follows: “And he said ‘Give me some of this red, because I am tired;’ therefore they called his name Red.”

The Meaning of a Name

The appellation for “Red” in this sentence, Edom, becomes the name of a nation at war with Israel throughout the Bible and later Rabbinic literature. Again we see that the stress is on ironclad destiny; Esau’s name is red, therefore he must act wildly and violently.

Does the Torah abandon us to this rigid view of history in which we are condemned to follow character traits impressed on us at birth? That there is an alternative approach is the major point of the second great story of Toldot, that of Isaac’s blessing of Jacob.

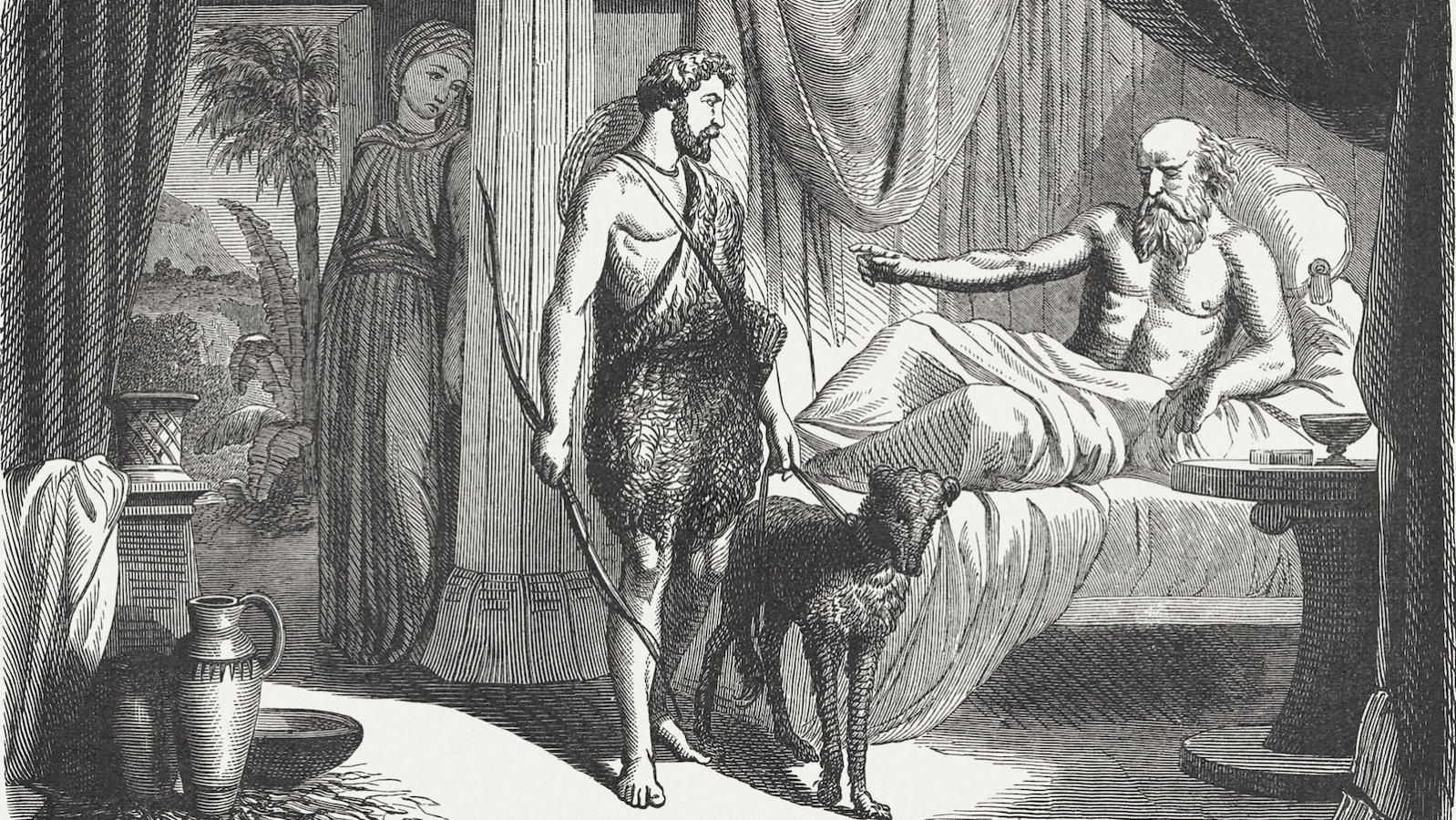

Isaac at first wants to confer the fateful blessing that will decide the future of Jewish history on Esau, his first born. Doing so would have reinforced the notion that fate is determined at birth. Since Esau is the first-born, he by nature receives the primary blessing.

But the Torah narrative overrides natural history and shifts the blessing to the younger son, Jacob. Thus, the seemingly ironclad rule of destiny as represented in primogeniture is shattered when Jacob and his mother Rebekah, acting on their sense of moral right, demonstrate that human action can defeat rigid fate. The story of Jacob’s blessing is an affirmation of the freedom of humans to act in the world according to their sense of right and justice and not be bound by seemingly natural laws like the privilege of the firstborn.

Women Altering Fate

This principle of the superiority of human freedom over blind fate is critical to the Torah, and it is repeated throughout Genesis. The younger son is favored over the elder in both the first set of brothers we meet in the text, Cain and Abel, and the last set, Ephraim and Menashe. This point is emphasized in Toldot though the juxtaposition of the theory of free history and the theory of unyielding destiny.

It is no accident that the chief orchestrator of the story of the blessing is a woman, the matriarch Rebekah. Frequently, when the Bible wants to shatter a pattern, it is a woman who will step forward to discard the old and champion innovative thinking. Thus, Sarah overrides Abraham’s clinging to primogeniture and insists that Ishmael leave the house so that Isaac can assume the mantle of Jewish leadership.

Later in the Bible, Hannah dismisses the advice of her husband, Elkanah, to be satisfied with her childless lot and prays for a son. The result is the birth of Samuel, the great prophet and reluctant innovator of kingship in Israel. Ruth punctures the Biblical prohibition against members of the nation of Moab entering into marriage with Jews; her descendants include Israel’s greatest king, David.

Overcoming the Ordinary

In each of these instances, the normal male-dominated world of the Bible is shaken by the emergence of a female who, through her decisive action, represents that everyday assumptions about the world can be broken by humans acting with a sense of purpose and justice.

The Bible places these two theories of history side-by-side. Both govern human behavior. In most cases, humans will follow natural rules such as primogeniture or make little effort to alter their basic characters. But Toldot teaches that we need not be constrained by rigid rules or personal habits. Like Jacob and the women of the Bible, we have the capacity to overcome the ordinary, achieve greatness and change the world.

Provided by the UJA-Federation of New York, which cares for those in need, strengthens Jewish peoplehood, and fosters Jewish renaissance.The following article is reprinted with permission from the UJA-Federation of New York.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.