Commentary on Parashat Shmini, Leviticus 9:1-11:47; Exodus 12:1-20

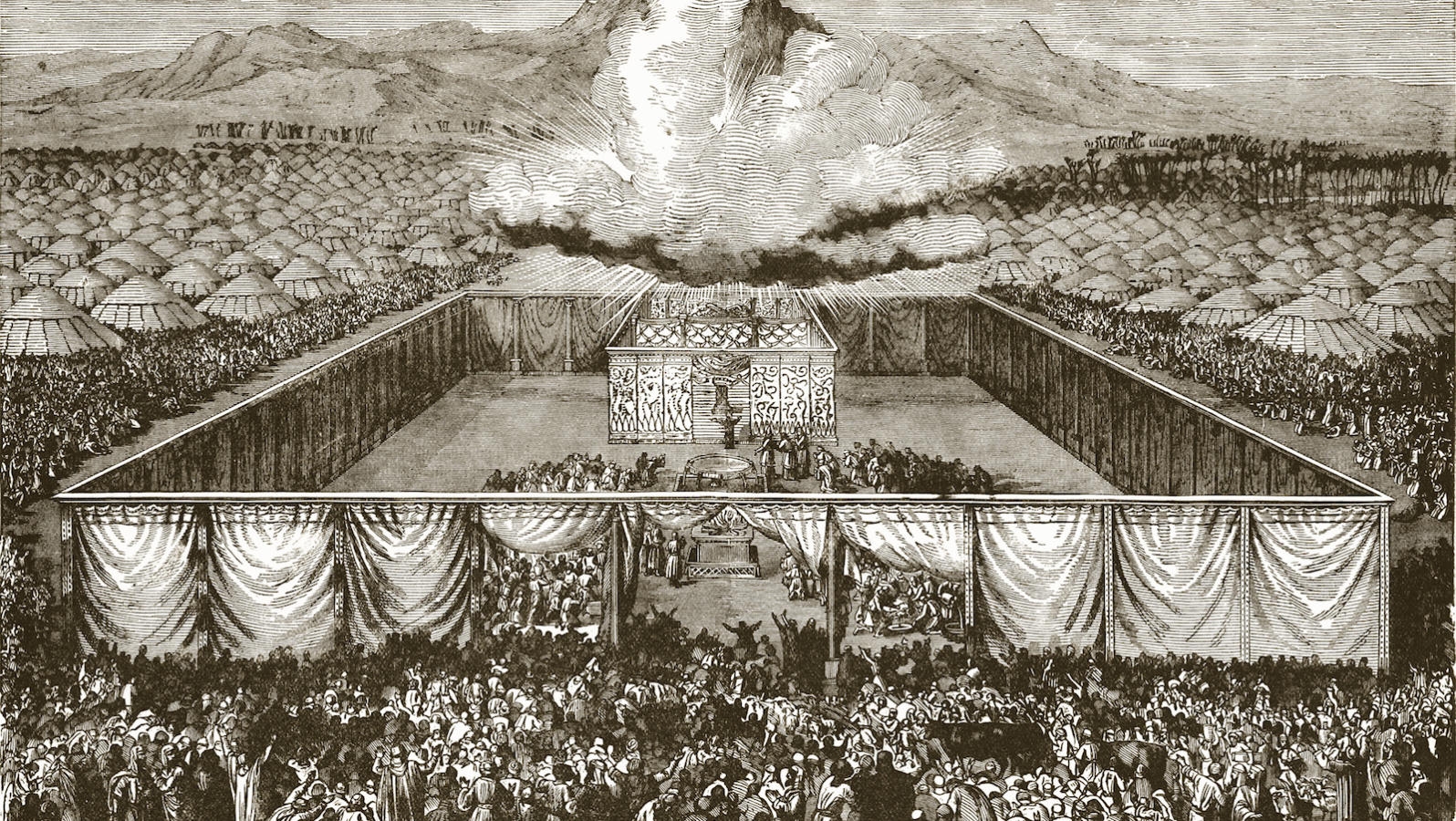

In last week’s Torah portion (Tzav), Aaron and his sons were dedicated as priests to serve in the Mishkan (Tabernacle). This week, in Shmini, the altar itself is dedicated, and the priestly service begins — but on a tragic note. Nadav and Avihu, Aaron’s sons, bring a “strange fire” on their own initiative, and die right then and there. God warns Aaron directly that priests may never perform their service while drunk. Rules are given for the disposition of the day’s korbanot (offerings/sacrifices). The last section of the parsha lists which animals, birds, fish and insects are permitted or forbidden as food.

In Focus

“Moses said to Aaron: ‘Approach the altar and make your sin-offering and your burnt-offering, to atone for yourself and for the people, and then offer the korban for the people, to atone for them, as God has commanded.’ ” (Leviticus 9:7)

What the Text Says

Moses instructs Aaron as the priestly service begins: First he must make a “sin-offering” for himself, and then a general sin offering for the Israelites. These offerings were made to atone for inadvertent or accidental transgressions; they are called chatat offerings, which is related to the more familiar word chet, which is often translated as “missing the mark.” After the sin-offerings, the regular sacrifices could begin.

Commentary

Once again our Torah portion study begins with a comment by Rashi (medieval French commentator) that gets expanded and explained by later scholars. Rashi picks up on the apparently superfluous phrase “approach the altar” in the verse quoted above. It’s not necessary to include this instruction — if Moses had simply said, “make your burnt offering,” Aaron would have to “approach the altar” to do it!

So Rashi sees the extra instruction — “approach the altar” — as a sign that maybe Aaron hesitated for a minute. Thus Rashi writes:

Aaron was timid and afraid to touch [it]. Moses said to him: “Why are you ashamed? For this you were chosen!”

Rashi’s comment can be read as simple encouragement; perhaps Aaron was in awe of his task, or didn’t feel confident, or didn’t know exactly what he was supposed to do.

On the other hand, all of those possibilities could be answered by noting that Moses and Aaron had been together all throughout the Exodus adventure, and had been through experiences like the plagues in Egypt, the splitting of the sea, and the giving of the Torah, any of which might have been more awe-inspiring than performing the priestly service!

Furthermore, Moses was right there to supervise. So it still begs the question: Why does Rashi think that Aaron might have hesitated at that moment, the moment of the inauguration of the Mishkan ceremonies?

A later commentator offers a psychological explanation of Aaron’s moment of holding back:

The Midrash says that the altar looked to him like a calf [i.e, that image filled Aaron’s mind], and that was why he hesitated. As is known, a person’s imagination is a product of those matters which are on his mind, and that’s what he dwells on. Aaron could not forget what happened with the Golden Calf–he always remembered this sin! This is like what is written: “My transgression is always before me.” (Psalm 51:5)

Thus, he saw the altar as a calf [again, that image was predominant]. Thus, when Moses said: “for this you were chosen,” he meant: “because of this, because you always remember your transgression and are humbled from it, you were chosen to serve as the High Priest.” (from Mincha Belulah, a 16th-century Torah commentary by the Italian rabbi Avraham Rapa, quoted in Itturei Torah. Translation mine.)

OK, now we’re getting somewhere. Rashi tells us that Aaron’s sin-offering was, in fact, a young cow; the Mincha Belulah postulates that the image of the cow made Aaron feel ashamed and unworthy, because he remembered his role in crafting the Golden Calf that Israel made while Moses was up on the mountain receiving the Torah. (See Exodus 32.)

The Mincha Belulah goes on to make a midrash (commentary) that it was precisely because of Aaron’s humility that God chose him to serve as the priest who atoned for the people.

To me, the Mincha Belulah’s midrash contains a twofold lesson. First, even Aaron, the High Priest, “misses the mark” sometimes; even Aaron has to bring the chatat offering for inadvertent transgressions. Yet even a lapse of good judgment as problematic as making the Golden Calf doesn’t mean one is banished from God’s Presence or disqualified from Divine service! The rest of us rarely craft idols which earn God’s fiery wrath (again, see Exodus 32-33), but we all make mistakes and “blow it” sometimes, and if Aaron can still approach God, then by all means, so can the rest of us.

The second teaching of our midrash concerns the importance of acknowledging our imperfections. Yes, we all make mistakes, and no, they don’t disqualify us from serving God, but recognizing our own fallibility its own form of spiritual growth. Aaron could be the one to bring the people close to God because had no illusions of being God himself — he knew (according to this reading) that he was just a mortal, imperfect person like anybody else, capable of mistakes, and just as capable of fixing them.

We might even theorize that it would be especially important for Aaron to have this kind of humility because he (and the other priests) would perform the “sin offerings” of the regular Israelites — and how could he help someone else put their mistakes behind them if he didn’t have empathy for what it felt like?

Coming to understand and accept our own imperfections and mistakes can help us feel compassion and empathy for our fellow fallible humans. Seen this way, the right kind of humility helps us come closer to God and others. The wrong kind holds us back, because we think that we’ve messed up so badly nothing can be done about it. To paraphrase Rabbi Nachman of Breslov: “If you believe you can sin, then believe you can fix what’s broken!”

Provided by KOLEL–The Adult Centre for Liberal Jewish Learning, which is affiliated with Canada’s Reform movement.

Avraham

Pronounced: AHVR-rah-ham, Origin: Hebrew, Abraham in the Torah, considered the first Jew.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.

Mincha

Pronounced: MINN-khah, Origin: Hebrew, the afternoon prayer service. According to traditional interpretation of Jewish law, men are commanded to pray three times a day.

parsha

Pronounced: PAR-sha or par-SHAH, Origin: Hebrew, portion, usually referring to the weekly Torah portion.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.