Commentary on Parashat Terumah, Exodus 25:1 - 27:19

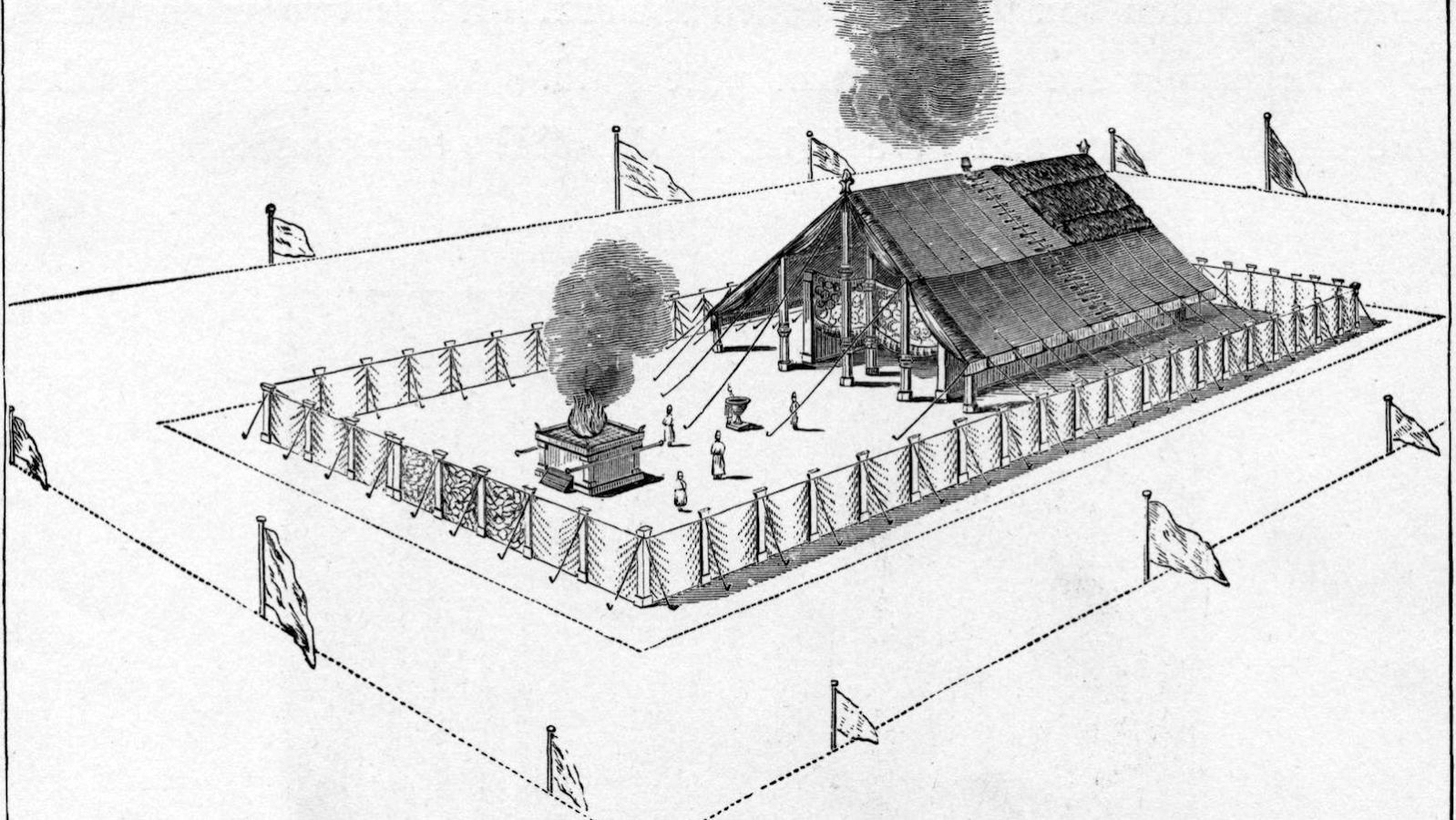

The purpose of the Exodus was always more than the liberation of the Hebrew slaves: It was the establishment of a physical existence in which HaShem would reign. And, at the center of that existence, would be the Mishkan (Tabernacle), the portable sanctuary:

And they shall make Me a Sanctuary, that I may dwell among them (Exodus 25:8).The establishment of the Mishkan will make it possible for Hashem’s Presence to dwell in the midst of the people.

Every aspect of the Mishkan teaches us how to serve HaShem.

How to Serve HaShem

The Mishkan would be the result of the collective efforts of the entire nation of Israel. It would be constructed from donations of their possessions and skills, and dedicated to the service of HaShem:

And Hashem spoke to Moses, saying: ‘Speak to the Children of Israel that they take for Me (v’yikchu li) a donation; from each man whose heart makes him willing shall you take My donation’ (Exodus 25:1-2).

Of course, one cannot really “give” to HaShem, since the whole world is His:

To Hashem are the earth and all that fills it, the habitation and those who dwell in it (Psalms 24:1).

Instead, one takes that which Hashem provides and devotes it to Him.

Rashi’s Views

Rashi‘s comment on the words v’yikchu li is famous for its brevity, and has stimulated much discussion by his commentaries: that they take for Me: for Me–for My Name.

What does Rashi wish to convey by his comment? How does he hope to shed light on the method of donating to the Mishkan? How does this explain the function of the Mishkan? And, what does this say about creating sanctity in our world?

To answer this, we must analyze how the items contributed for the building of the sanctuary progress from being simple raw material to becoming objects of intrinsic holiness.

Remember that, once something is sanctified by a human declaration (hakdashah), it may not be utilized for any personal use, for then one would be guilty of me’ilah, misappropriation of holy objects. If done intentionally, me’ilah carries with it the penalty of lashes plus the requirement to compensate. Even if done unintentionally, one would have to pay for the benefit plus one-fifth, as well as bring a sacrifice (asham me’ilah).

Because of the severity of me’ilah, writes the Rambam,

When they build the sanctuary, they do not take wood and stones from sanctified items, nor do they build the building with the intention that it is holy; rather, they build everything from the unconsecrated. This is a decree, lest one benefit from the shade of the building, or lean on a stone or a beam during the time of the work (Laws of Me’ilah 8:4).

Since “The Torah was not given to the ministering angels” (Me’ilah 14a), but to human beings, such use would be unavoidable. Only after the building is complete would they sanctify their work.

R. Tzvi Yehudah Kook (1891-1982), in Torat Eretz Yisrael (pp. 347-348), says that, just as the sanctuary was built in gradual stages, so is the redemption of Israel and the building up of the Land of Israel in our time. The secular foundation of the modern State of Israel lays the groundwork for ultimate sanctity. We build with the non-holy until such time that “the sanctification of Hashem will appear in more and more light.”

However, the construction materials of the Mishkan, while unconsecrated, are nonetheless earmarked for eventual consecration:

Initially, we do not make any of the utensils except for the sake (l’shem, literally for the name) of holiness. And if they were initially made for lay use, we cannot transform them into use for the Most High (Laws of the Temple 1:20).

Even these unconsecrated raw materials must be designated l’shem ha’kodesh, for the sake of holiness.

Thus, every item donated for the Mishkan passes through three stages:

1. L’shem hakodesh–designated for holiness.

2. Construction.

3. Mukdash–consecrated.

A piece of acacia wood, for example, (Shemot 25:5) begins at the “l’shem” stage of sanctity, although it is not yet sanctified: If the workers lean on it during the construction, they have committed no me’ilah. Only after the craftsmen have made it into part of the Holy Ark (verses 10-16), is it rendered sanctified by their act of sanctification and initiation.

It is in this light that Rashi should be understood. Hashem commands that they take for Me (v’yikchu li) a donation, meaning “for Me–for My Name.”

Leading to Sanctity

This is the first stage that leads to complete sanctity. In clarifying this requirement, R. Yechiel Michel Epstein (1829-1908), in Aruch HaShulchan He-Atid, posits that l’shem ha’kodesh means that the materials must be merely not explicitly designated for personal use.

Even at the stage when the donated materials are chol, unconsecrated, Hashem wants them to be directed away from self-centeredness. They must be open to and directed towards holiness–to be simultaneously part of the mundane and reserved for the service of Hashem.

There is a tendency to think that there are two distinct, even antithetical, spheres of existence–the sacred (kodesh) and the profane (chol)–but this is not so. Chol and kodesh are not binary values, but rather the starting and end-points on a continuum.

The construction of the Mishkan teaches that, even when we are involved in the everyday activities of life, we have the ability to be oriented to the holy. We are able, and we are challenged by Hashem to live every moment of our lives in a way that prepares for sanctity. The building of the Mishkan on earth begins with the building of a Mishkan in our hearts.

Provided by the Orthodox Union, the central coordinating agency for North American Orthodox congregations.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.

HaShem

Pronounced: hah-SHEMM, Origin: Hebrew, literally, “the name,” word used to refer to God.