Commentary on Parashat Vaetchanan, Deuteronomy 3:23 - 7:11

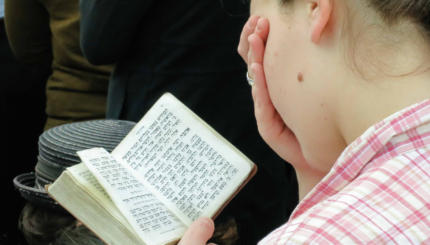

The Torah portion Vaetchanan contains the Shema, one of the great foundational statements of the Torah:

Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Echad

Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.

For centuries the watchword of the Jewish people, the Shema has had a resonance and power unmatched by any other statement in Judaism. Books and commentaries have been written about it; countless Jewish children have learned the Shema as their first prayer; countless Jews have died with the Shema on their lips.

But the subtleties of meaning conveyed by the six words of the Shema have changed over time. The earliest understanding — at a time when the Israelites were surrounded by pagan civilizations — may have been along the lines of “Hear O Israel, Adonai is our God, only Adonai.” In other words, among all the other gods around, only Adonai is the Israelite God. Over time, as pagan gods faded away, the Shema took on a subtly different meaning — that while Adonai is our God, in time Adonai will come to be acknowledged by everyone as the one and only God.

Another strain of thought, which has had a resurgence of popularity in recent years, focuses on the different aspects of divinity implied by the terms Adonai (Lord) and Elohim (God). While Elohim relates to the timeless, cyclical manifestation of God in the natural universe, Adonai is the Jewish God of transformation, the God who makes a difference, who liberates from slavery and brings about healing and creativity. As Rabbi Harold Schulweis has written in For Those Who Can’t Believe, “divinity includes both the reality principle of Elohim and the ideality principle of Adonai. Adonai is the source of healing; Elohim, the life of the universe.”

And, says the Shema, both aspects are joined in the Divine. Adonai and Elohim are one and the same. What a radical notion that is, what a radical statement about the universe the Shema becomes: yes to reality, and yes to transformation! Yes to nature (including human nature) and yes to healing. Yes to unchanging permanence and yes to constant becoming — ehyeh asher ehyeh, God’s self-proclaimed name: “I will be what I become.”

The Shema can be seen as a fundamental principle for grounding social action and social transformation in a deep understanding of the limits of what is, as well as a boundless optimism for what can yet be achieved. In a conversation about the concept of Adonai and Elohim with the late Rabbi Ira Eisenstein, alav ha-shalom (may he rest in peace), he once remarked,

Adonai in a sense is fighting Elohim to let people live. You look at Elohim — you see disease, earthquakes, people dying. If you didn’t find a trace of Adonai, you’d be living in a godless world. But the Adonai side is the difficult side. Mordecai Kaplan would say that you have to seek out those aspects of reality that make for salvation. There is a verse in [this week’s portion of] the Torah that says: ‘You will find Him if you search for Him with all your heart and spirit’ (Deuteronomy 4:29).

The opening of the Shema calls on us to develop this understanding as a community. As Harold Fisch has written in Poetry With a Purpose, “The divine unity is realized only when there is a community of hearers to achieve that perception, to make that affirmation; it is a perception that has to be striven for, created in the act of reading, hearing, and understanding.”

How do we actualize that understanding of divine unity? The answer comes immediately following the Shema: through love. “Ve’ahavta et Adonai Elohecha, you shall love the Lord your God.”

One wonders how the Torah can command a person to love. Rabbi Norman Lamm in his book The Shema, cites Rabbi Shneur Zalman as saying: “We are not commanded to impose upon ourselves an extraneous, extra-human sentiment; rather, this love for God already exists in potential form… within our soul. The mitzvah to love God demands that we remove all obstacles and impediments that interfere with our free and open expression of that love.”

An ancient book of midrash offers another interpretation of “ve’ahavta.” The Sifre interprets “you shall love the Lord your God” as meaning: you shall cause God to be beloved by human beings. Perhaps, then, the “ve’ahavta” in this week’s parasha is predicated on another ve’ahavta from the Book of Leviticus: “Ve’ahavta le’rayacha kamokha, you shall love your neighbor as yourself.”

Only by acting in the world with compassion, and treating one another with justice and equality will the healing aspects of God become manifest and draw others to a deeper understanding and love of God. To “love God” we must act with loving intention towards all of Creation.

Reprinted with permission from SocialAction.com.

Adonai

Pronounced: ah-doe-NYE, Origin: Hebrew, a name for God.

mitzvah

Pronounced: MITZ-vuh or meetz-VAH, Origin: Hebrew, commandment, also used to mean good deed.

Shema

Pronounced: shuh-MAH or SHMAH, Alternate Spellings: Sh’ma, Shma, Origin: Hebrew, the central prayer of Judaism, proclaiming God is one.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.