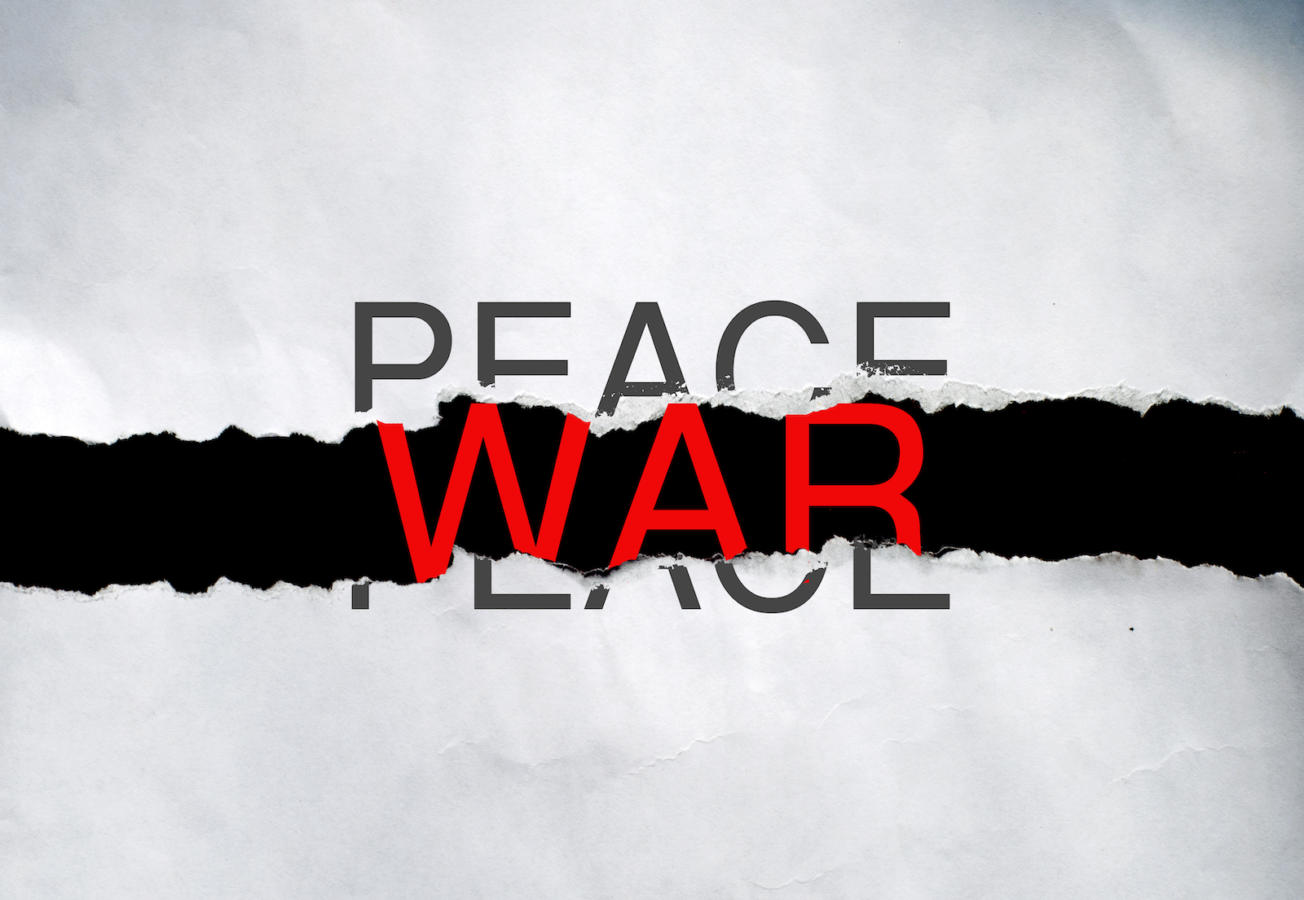

The Hebrew word for peace, shalom, denotes a sense of completion, perfection — shlemut (“wholeness”). In fact, in the Bible, shalom means “well-being” or “prosperity,” not just “peace.”

Thus, in Judaism, peace is not only the opposite of war, it is an ideal state of affairs. In this sense, peace — perfection — is something that will not be totally achieved until the messianic era. When the Messiah comes, “nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore” (Isaiah 2:4), but this will be part of a general societal harmony and perfection.

The fact that true peace is an eschatological dream, however, does not mean that it is not a Jewish value in the present. In the Talmud, peace is one of the most esteemed values.

According to Rabbi Simeon ben Gamliel, three things preserve the world: truth, justice, and peace (Avot 1:18). Peace, however, seems to take precedence even over truth, as the Talmud permits deviation from truth in order to establish peace. In addition, there is a whole category of rabbinic ordinances established mipnei darkhei shalom, in the interest of peace. And there is also a concept of shalom bayit — peace in the home — which refers to the interest of family living together in harmony.

There is even a sense that peace is more important than loyalty to God. In response to Hosea 4:17 (“Ephraim is joined to idols: let him alone.”), the Midrash says, “even if Israel is tied to idols, leave him, as long as peace prevails within it” (Genesis Rabbah 38:6). Elsewhere the Talmud says, “If in order to establish peace between husband and wife, the name of God, which was written in holiness, may be blotted out, how much more so to bring about peace for the world as a whole.” (Shabbat 116a)

Perhaps nothing exhibits the importance of peace more than the fact that almost every major Jewish prayer — the Amidah, Kaddish, Priestly Blessing, Grace After Meals — concludes with an appeal for peace.

And yet, Judaism is hardly pacifistic. There are clearly times when Judaism permits and even requires war. Jews have on occasion embraced nonviolence, even martyrdom, as a response to conflict, but not out of a sense that violence is categorically inappropriate, rather because in those situations nonviolence was the best tactical option. Nonetheless, the minimization of violence is certainly a Jewish value.

Avoiding Conflict and Violence

Indeed, when war is declared, the Torah requires that peace be offered prior to commencing an attack. “When you come near to a city to fight against it, then proclaim shalom to it” (Deuteronomy 20:10). Admittedly, in this context, shalom means something more like “submission” than “peace.” Nonetheless, biblical morality opposes a violent solution when a nonviolent solution is possible.

In addition, the rabbis of the Talmud established parameters for discretionary wars of aggression that make them virtually impossible to declare today. For one, the Sanhedrin (the traditional Jewish high court) must be consulted. Today there is no Sanhedrin, though some thinkers would extend this ruling to any equivalent body of representation, such as the Israeli Knesset (parliament). In addition, the urim v’tumim, the priestly breastplate and oracle, must be consulted to determine the probability of victory. The urim v’tumim, however, no longer exist.

Finally, permitted wars do not trump obligations to fulfill commandments, and thus one is not allowed to begin a non-commanded war (i.e., any war that is not either defensive, or against the seven nations of biblical Israel or the biblical nation of Amalek) unless it is probable that commandments will not need to be transgressed. This is hardly feasible (imagine a war that takes a break every Saturday!).

Some People Don’t Have to Fight

The laws of war listed in Deuteronomy include a list of those exempt from battle. The Talmud extends all these exemptions, and notes that they only apply to discretionary wars. In commanded wars, “all go forth, even a bridegroom from his chamber and a bride from her canopy.” (Sotah 44b)

Broadly speaking, exemptions were granted to those who were in the midst of a lifecycle event, those who have “built a new house but has not dedicated it…or planted a vineyard but has never harvested it…or spoken for a woman in marriage but has not married her.” (Deuteronomy 20:5-7) In addition, the Torah provides exemptions for the fearful and the tender-hearted. Most scholars and rabbinic authorities believe that these psychological exemptions were meant to exclude soldiers whose attitude would hurt the morale of the army.

However, others — such as Arthur Waskow — have suggested that this exemption is akin to an exemption for conscientious objectors.

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.