In the Jewish tradition, humility is among the greatest of the virtues, as its opposite, pride, is among the worst of the vices. Moses, the greatest of men, is described as the most humble: “Now the man Moses was very meek, above all the men that were on the face of the earth (Numbers 12:3).” The patriarch Abraham protests to God: “Behold now, I have taken upon me to speak unto the Lord, who am but dust and ashes (Genesis 18:27).”

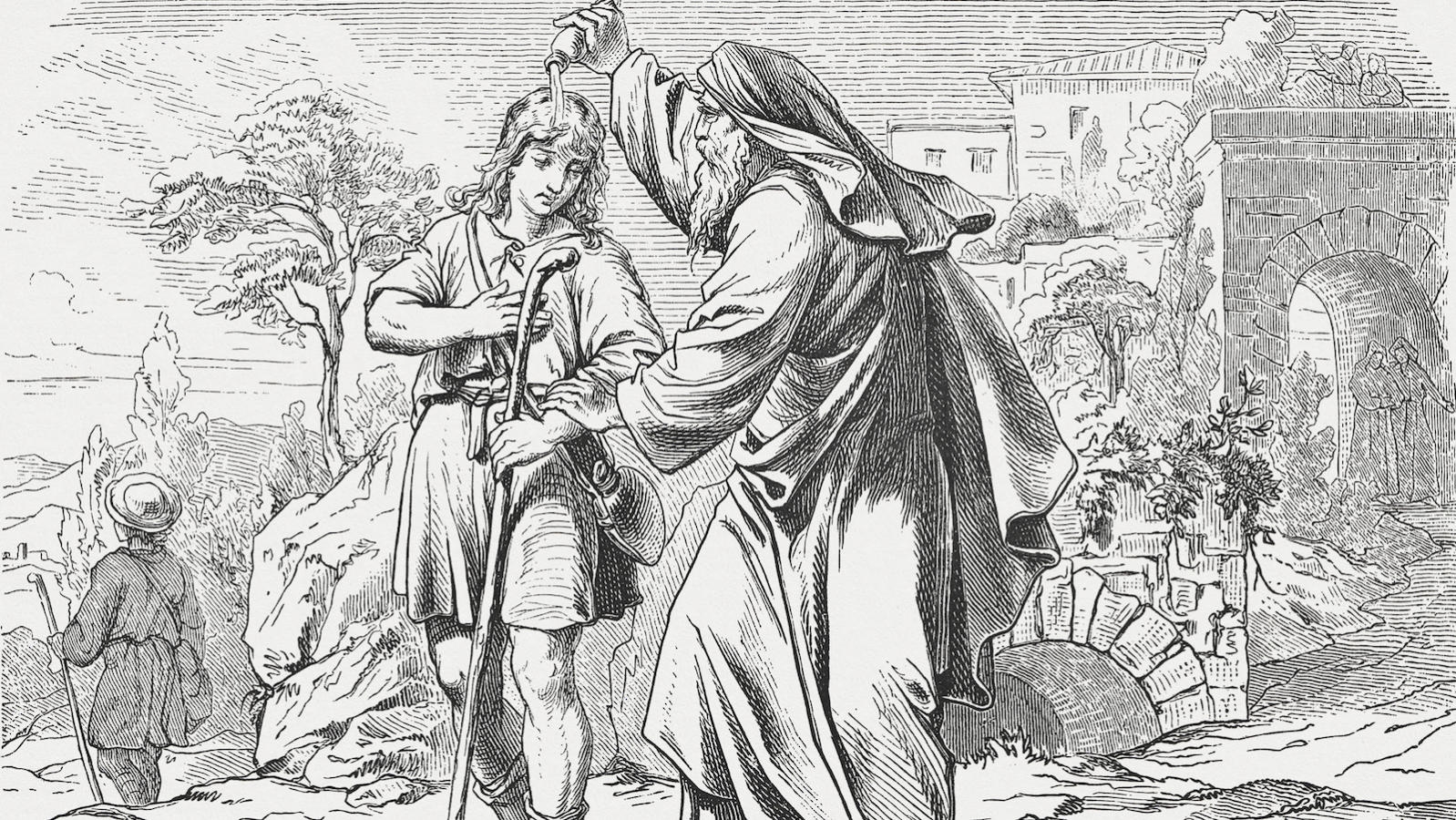

When Saul was chosen as Israel’s first king, he was discovered “hid among the baggage (I Samuel 10:22),” a phrase which became current among Jews for the man who shuns the limelight. The Hebrew king was to write a copy of the law and read therein all the days of his life, “that his heart be not lifted above his brethren (Deuteronomy 17:20).”

Greatness and Humbleness

Greatness and humility, in the Jewish tradition, are not incompatible. They complement one another. For a man to be humble he does not have to be someone who “has plenty to be humble about,” as Churchill is reported to have said of a political opponent who was praised for his humility. The greater the man the more humble he is expected to be and is likely to be. The Torah, say the rabbis (Taanit 7a), is compared to water for just as water only runs downhill, never uphill, the word of God can only be heard in a humble heart.

The Jewish moralists are fully aware that any conscious attempt to attain to humility is always self-defeating and that pride can masquerade as humility. Crude vanity and self glorification are easily recognized for what they are. Mock modesty is less easy to detect. It is not unusual for a man to take pride in his humility; nor is it unknown for a man to indulge in the more subtle form of self deception in which he prides himself that he is not a victim of false modesty.

Luzzatto’s View

In his Path of the Upright, Moses Hayyim Luzzatto has an amusing analysis of various forms of false modesty: “Another imagines that he is so great and so deserving of honor that no one can deprive him of the usual signs of respect. And to prove this, he behaves as though he were humble and goes to great extremes in displaying boundless modesty and infinite humility. But in his heart he is proud, saying to himself: ‘I am so exalted, and so deserving of honor, that I need not have anyone do me honor. I can well afford to forgo marks of respect.’

Another is the coxcomb, who wants to be noted for his superior qualities and to be singled out for his behavior. He is not satisfied with having everyone praise him for the superior traits he thinks he possesses, but he wants them also to include in their praises that he is the most humble of men. He thus takes pride in his humility, and wishes to be honored because he pretends to flee from honor. Such a prig usually goes so far as to put himself below those who are much inferior to him, even below the meanest, thinking that in this way he displays the utmost humility. He refuses all titles of greatness and declines promotion in rank, but in his heart he thinks, ‘There is no one in all the world as wise and as humble as I.’ Conceited people of this type, though they pretend mightily to be humble, cannot escape some mishap which causes their pride to burst forth, like flame out of a heap of litter.”

Hasidic Perspective

A Hasidic tale tells of a man who came to the Zaddik with a complaint. “All my life,” he said, “I have tried to follow the advice of the rabbis that one who runs away from fame will find that fame pursues him, and yet while I run away from fame, fame never seems to pursue me.” The Zaddik replied: “The trouble is that while you do run away from fame you are always looking over your shoulder to see if fame is chasing after you.”

It is a paradox in the whole matter of humility that when a man knows his own worth he comes close to being a victim of pride and yet humility cannot mean that a man has to imagine that he is less worthy than he really is. Self-delusion is no virtue and is presumably to be as much avoided as any other delusion by the seeker after truth. “The last infirmity of great minds” is not easily conquered.

This is how Nahmanides deals with the problem of humility in a famous letter he wrote to his son: “I shall explain how you should become accustomed to the practice of humility in your daily life. Let your voice be gentle, and your head bowed. Let your eyes be turned earthwards and your heart heavenwards. When you speak to someone do not look him in the face. Let every man seem superior to you in your own eyes. If he is wise or rich you have reason to respect him. If he is poor and you are richer or wiser than he, think to yourself that you are therefore all the more unworthy and he all the less, for if you sin you do so intentionally whereas he only sins unintentionally.”

Modern readers will no doubt find Nahmanides’ treatment extreme. Is it possible or even desirable never to look another in the face? Such an attitude will often be insulting. Basically, what Nahmanides seems to mean is that God alone knows the true worth of a man and the extent to which he faces life’s challenge with the gifts, or lack of them, that are his fate. The religious basis for humility is that only God knows the true worth of each human being.

On the deeper level, the notion is found, especially in Hasidism, that humility is not the mere absence of pride. Rather it consists not so much in thinking little of oneself as in not thinking of oneself at all. When the Hasidim and other Jewish mystics speak of annihilation of selfhood, they are not thinking of a conscious effort of the will. To try to nullify the self by calling attention to it is bound to end in failure. Instead, the mystics tend to suggest, the mind should be encouraged to overlook entirely all considerations of both inferiority and superiority.

Reprinted from The Jewish Religion: A Companion, published by Oxford University Press.

Hasidic

Pronounced: khah-SID-ik, Origin: Hebrew, a stream within ultra-Orthodox Judaism that grew out of an 18th-century mystical revival movement.