Commentary on Parashat Ha'Azinu, Deuteronomy 32:1 - 32:52

- Moses sings his last song, a love poem to God and a chastisement of the people, who are not worthy of Adonai. (32:1–6)

- The poem recounts the blessings that God has bestowed on the Israelites, the wicked deeds they have committed, and the punishments that God then inflicted upon them. (32:7–43)

- God tells Moses to begin his ascent of Mount Nebo, from where he will see the Land of Israel from a distance but will not be allowed to enter it. (32:45–52)

Focal Point

Give ear, O heavens, let me speak;/Let the earth hear the words I utter!/May my discourse come down as the rain,/My speech distill as the dew,/Like showers on young growth,/Like droplets on the grass./For the name of Adonai I proclaim…. Take to heart all the words with which I have warned you this day. Enjoin them upon your children, that they may observe faithfully all the terms of this Teaching. For this is not a trifling thing for you: It is your very life; through it you shall long endure on the land that you are to possess upon crossing the Jordan (Deuteronomy 32:1–3; 45–47).

Your Guide

Why does Moses invoke heaven and earth when it is the Israelite people whom he is addressing?

How does Moses convey his humanity in this song? Why would Moses think that his final words might be regarded as “trifling” by his audience? How does the water imagery in Moses’ description of the Torah make his point? In what way does this closing statement about enduring on the land attempt to balance the reality of Israel’s exile in Egypt? Why does Moses address the heavens at the start of his song and address the Israelites directly at its conclusion?

By the Way…

Sons, heed the discipline of a father. Listen and learn discernment, for I give you good instruction. Do not forsake My teaching (Proverbs 4:1–2).

Honor your father and your mother so that you may long endure on the land that Adonai your God is giving you (Exodus 20:12).

“It is your very life” (Deuteronomy 32:47). A person who leaves a child like himself [or herself] is not considered to have died. That being the case, a person lives eternally through the Torah (Shlomo Kluger in Torah Gems, vol. III, p. 328).

Your Guide

In Proverbs 4:1–2, sons are instructed to heed the discipline of a father. In his song, Moses instructs the Israelites to take all his words to heart. What are the similarities in these two texts? Does Moses regard the Israelites as his children?

How can the ability to separate a role from a person, as in honoring one’s parents despite their mistakes, strengthen individual and societal life?

Do you agree with Kluger that “a person lives eternally through the Torah?” Did Moses achieve this?

Commentary

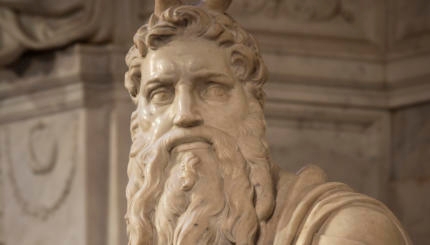

We come now to Moses’ final words. Moses stands at the edge of his life, ready to accept the isolation of the present moment. He seeks the rapt attention of all that is around him–the heavens, the earth, the elements, the nations of the world, certainly Israel, and most certainly God.

As an adult, I have never been able to read this text without recalling the famous opening line of the speech by Mark Antony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears. I have come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.”

Mark Antony’s purpose in delivering his speech is very different from the one he claims to have in the opening line: What he is set on doing is instilling a sense of shame in his audience for the betrayal of greatness, for the besmirching of Caesar’s name. Moses, too, has a very different purpose for his speech than simply to praise God.

Moses wants to give the people a distillation of everything he has learned over the course of his eventful life. He wishes to provide the Israelites with the greatest of impossibilities — a degree of certainty in their fragile lives. In this moment, when he is approaching the end of his life, he seeks to leave behind some assurance for his spiritual children that if they avoid the mistakes he has made, they will attain an intimate relationship with the divine territory that he has been denied.

So what does remain for us, the generations that have followed, the children that have been taught? Surely not the ability to avoid the mistakes our forebears have made. Over and over again, we continue to commit the same ones. Just like our ancestors, we overstep boundaries, engage in excess, remain overly attached to old successes, and often fail to live in our present experience. As a result, we are left hungry and thirsty, with a need to acquire things and to fill the void within us with possessions and activities.

But Moses has yet another lesson for us — one that can quench our thirst and provide us with a balm for our pain. He offers us the opportunity to connect with the passion that he expresses in this magnificent poem. Like Moses, we can understand how much the earth, the young trees, and the grass yearn for moisture. We can reflect on our own complacency and comprehend how misguided we have been. We can look out into a future that is far beyond our reach and see and love the generations that will follow.

Then we can turn to the Torah, consider the roles we were meant to play, and find a way to transform the empty thirsty beings that we have been into ones worthy of populating a land flowing with milk and honey.

Provided by the Union for Reform Judaism, the central body of Reform Judaism in North America.

Adonai

Pronounced: ah-doe-NYE, Origin: Hebrew, a name for God.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.