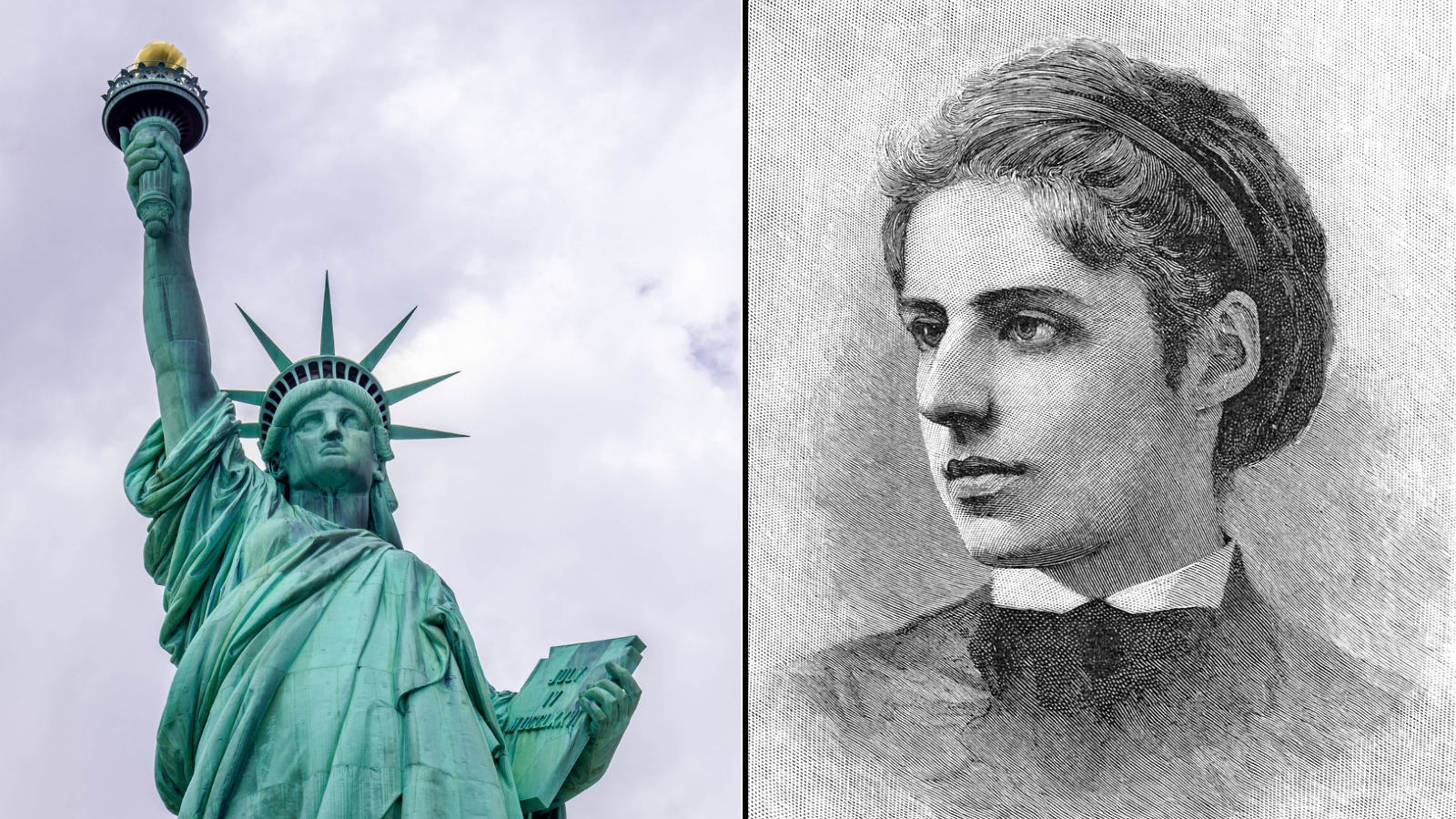

A poet devoted to recounting and romanticizing the life of the immigrant — her work even included on the base of the Statue of Liberty — Emma Lazarus (1849-1887) was herself no immigrant. Her father was a wealthy sugar merchant, and she was raised in New York and Newport, schooled by tutors who taught her music, literature, and poetry. Poetry caught Lazarus’ attention, and by 1866, at the age of 17, she was publishing her own, in a volume called Poems and Translations: Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Sixteen.

Lazarus was a classicist, her poems making reference to Greek and Roman history, as well as the life of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Above all, though, she was a potent recycler of Jewish history. Inspired by the horrific Russian pogroms of 1881, Lazarus redoubled her rhetorical commitment to her heritage, eschewing the polite, deracinated Judaism of many of her peers. Lazarus penned “The Dance to Death,” a quasi-archaic verse play set in medieval Germany and sparked by those same Russian pogroms. The play was dedicated to George Eliot, author of the Jewish-themed novel Daniel Deronda, “who did most among the artists of our day towards elevating and ennobling the spirit of Jewish nationality.”

In Songs of a Semite (1882), her most famous full-length work, Lazarus celebrates Jewish resilience in the mock-archaic tones of the King James Bible. The mood of Songs of a Semite echoed her earlier poem “In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport” (1867), which inverted Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s grim “The Jewish Cemetery at Newport” and reached a starkly different conclusion: “the sacred shrine is holy yet.”

Songs of a Semite, as its blunt title indicates, was not written from any sort of defensive crouch. Instead, Lazarus was celebrating her own roots, and what she saw as the best of her heritage. Lazarus was singing, “In Exile,” of “Freedom to love the law that Moses brought/To sing the songs of David, and to think/The thoughts Gabirol to Spinoza taught.”

Lazarus’ Judaism was multifaceted, equal parts philosophy, music, and jurisprudence. It was also, however, a story of homelessness and hatred: “Once more the clarion cock has crowed,/Once more the sword of Christ is drawn./A million burning rooftrees light/The world-wide path of Israel’s flight./Where is the Hebrew’s fatherland?” The Jews were downtrodden, weary, their grandeur sapped by anti-Semitism and exile, and yet there was still an aura to the Jew that persisted, no matter the horrors of the past. “Oh deem not dead that martial fire,/Say not the mystic flame is spent!/With Moses’ law and David’s lyre,/Your ancient strength remains unbent./Let but an Ezra rise anew,/To lift the Banner of the Jew!”

Lazarus’ last work, By the Waters of Babylon, published posthumously in 1888, continued in the vein of Songs of a Semite, beginning with “The Exodus (August 3, 1492),” which depicted the forced exodus of Spanish Jewry in the same year as Christopher Columbus had his famous “exodus.”

“Daylong I brooded upon the passion of Israel,” begins “The Test,” and “The Prophet” continues with a lovingly compiled array of Jewish luminaries. “1. Moses ben Maimon lifting his perpetual lamp over the path of the perplexed;/ 2. Hallevi, the honey-tongued poet, wakening amid the silent ruins of Zion the sleeping lyre of David;/ 3. Moses, the wise son of Mendel, who made the Ghetto illustrious.”

For all of Lazarus’ poetic work, the one she is best known for is most famous for appearing not on a page, but on a statue. Etched into the side of the Statue of Liberty are the verses that pay passionate tribute to the immigrant ideal that had spurred the United States. “The New Colossus,” written for the Statue of Liberty as part of a fundraising effort for its pedestal, imagined a larger-than-life woman, “Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,” standing guard over the entrance to the United States, “whose flame/Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name/Mother of Exiles.” Lazarus was purposefully vague, but “The New Colossus” was clearly inspired by the Jewish immigrants she had paid lavish tribute to in her poetry.

Lazarus was offering her country a mantra, open-hearted words to live by:

“Give me your tired, your poor,/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,/The wretched refuse of your teeming shore,/ Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,/ I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Emma Lazarus died in 1887, at the age of 38, a scant four years after “The New Colossus” was published, and 16 years before it appeared on Lady Liberty. Her career was short lived but dazzling. Lazarus is remembered for her ode to America’s newest arrivals, but her poetry remembers the old world they left behind as well.