Commentary on Parashat Vayeshev, Genesis 37:1 - 40:23

This week’s Torah reading presents us with three stories of justice and injustice. In each, an individual or group is faced with circumstances they believe to be harsh and unjust, and — believing that there is no recourse except to take matters into their own hands — undertakes extra-judicial activity.

The outcome of each case sheds some light on the relativity of justice, the process by which justice is achieved, and the human factors that mediate absolute rules and inflexible systems. Each case also speaks to the failings of both human nature and our modern justice systems.

Jacob’s Favoritism and The Brothers’ Jealousy

In the first story, Joseph’s brothers punish both their father and brother for perpetuating unfairness. Jacob shows favoritism towards Joseph, deploys him to report on his brothers, and gives him a special coat that is unlike anything his brothers own. The tension is exacerbated when Joseph dreams of his own superiority and eagerly shares the vision with his family.

Joseph’s brothers find his presence to be a constant reminder of their inferior status, and their revenge is calculated and cruel. They force Joseph into a pit with no food or water and plot to kill him while they feast, then bloody Joseph’s coat and inform their distraught father that his favorite son has met a cruel death.

Only two out of the eleven brothers show any mercy. Reuben plots to foil their plan, and Judah appeals to his brothers’ self-interest and offers a compromise: selling him into slavery. He appeals both to their sense of brotherly duty and their fear of judgment. The plea bargain is successful; Joseph’s life is spared and he is sold into slavery. Interestingly, it is Judah’s pragmatic approach (and not Reuben’s pure motives) that calms the mob and mediates vengeance.

Tamar Takes Action

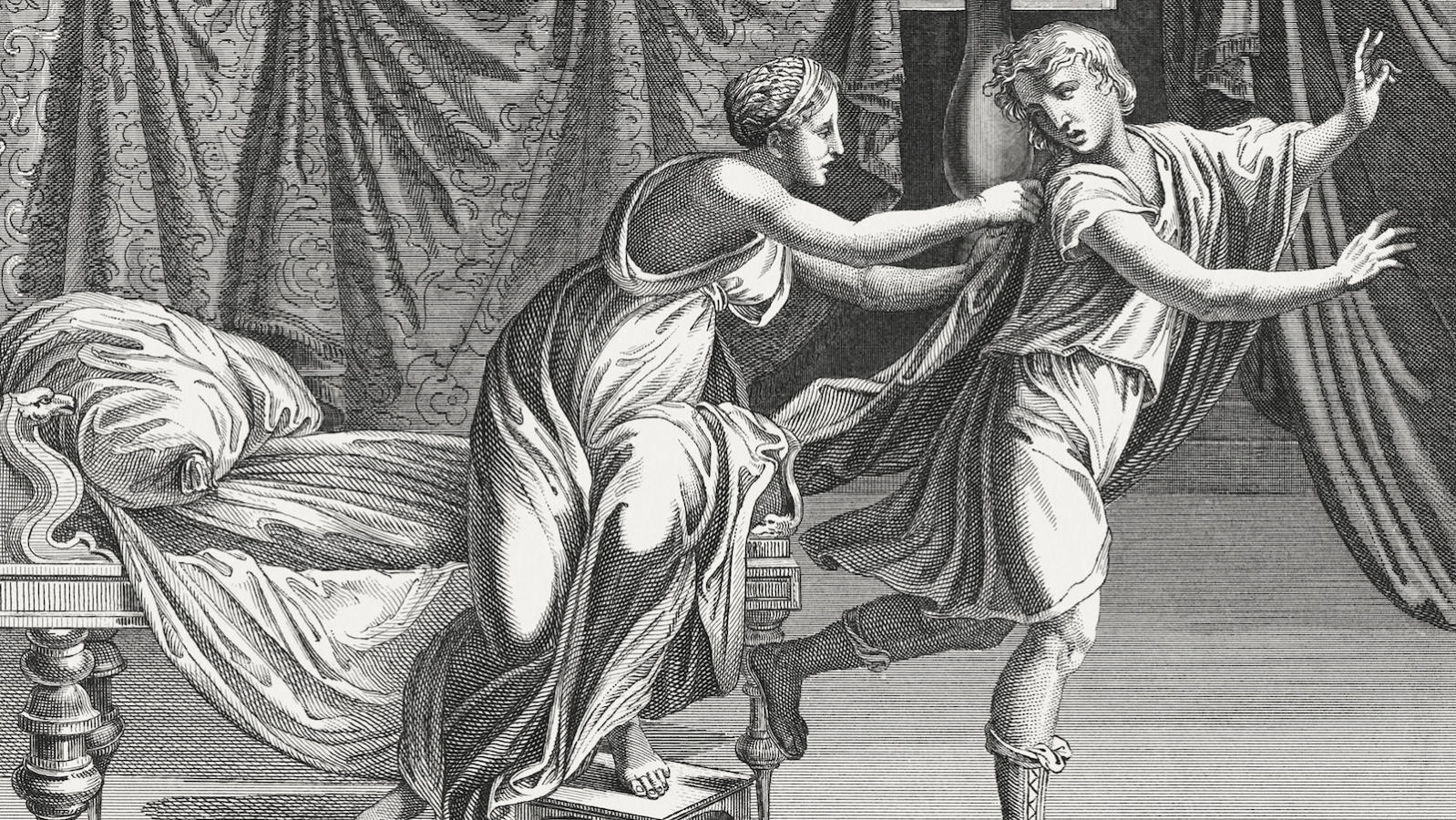

In the second story, Tamar’s husband is killed and she is left without a means of support and capacity to reproduce, because her father-in-law does not fulfill his promises (and legal obligations). She carries out a deception (including posing as a prostitute and seducing her father-in-law) which, while clearly transgressive, ultimately achieves the goals of bringing her offspring and binding her to the house of Judah.

The system designed to protect Tamar failed her. The ancient practice of promising a younger sibling to the wife of a deceased brother was intended to secure the widow’s socioeconomic status, and when Judah does not fulfill his obligations, Tamar deceives him to restore justice and take her due. She achieves an end that brings positive resolution to her plight and asserts her personal righteousness. Despite her methods, Tamar is rewarded for her resourcefulness with a child, with Judah’s apology, and with the implicit approval of the Torah’s narrative.

Mrs. Potiphar’s Act of Injustice

In the final vignette, Joseph, now in Egypt, is a loyal slave. When the wife of his master, Potiphar, tries to seduce him, he resists her advances. She is infuriated, falsely accuses him of rape, and has him thrown in prison. Mrs. Potiphar, who is wealthy, well-connected, and manipulative, is able to make the system work in her favor and deny Joseph a fair hearing. Though Joseph has done nothing wrong and has been an exemplary servant, he is convicted and punished.

These seemingly unrelated stories are linked by their focus on justice and injustice. In the first vignette, we are presented with the basic injustice of harsh punishment: Joseph and his father have behaved without sensitivity, but their punishment is wildly disproportionate to the offense — and the only thing that mediates the brothers’ harsh judgment is their self-interest. Joseph and Jacob alone did not create this dynamic; it is the unconscious conspiracy of an entire family, demonstrating how easy it is to gravitate towards harsh and punitive responses and ignore the complexity and causes of apparent injustice.

The second vignette reminds us that systemic justice operates beyond the courtroom, in social systems intended to foster fairness and protect the vulnerable, with their own potential for incomplete justice. Judah ignores his obligations and nearly compounds tragedy by punishing the victim. Tamar is rewarded for her resourcefulness and perseverance, but she pays the price of her dignity.

Protecting the Vulnerable

In contemporary welfare systems, too, the vulnerable are often doubly punished by systems tangled in red tape, that so often place too much power in the hands of capricious bureaucrats and fail to protect the dignity of beneficiaries.

In the third vignette, the justice system is inherently unjust in its application. All who come before it are not on equal standing: the one with wealth and power holds undue influence, and the character and prior record of the accused is not considered. A system of true justice would strive to be impervious to corruption, and guard against the subversion of fairness by those with wealth and power.

Justice is complex. Human nature is flawed. Systems are vulnerable to abuse. Parashat Vayeshev urges us to be vigilant — to create systems of justice that take into account root causes, and do not punish victims or allow vengeance to prevail; to see that good systems are enforced and that vulnerable members of society are treated with dignity; and to ensure that power and wealth do not hold undue influence, and that all are equal before the law.

Provided by SocialAction.com, an online Jewish magazine dedicated to pursuing justice, building community, and repairing the world.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.